How ISOs and RTOs are Addressing Large Load Growth

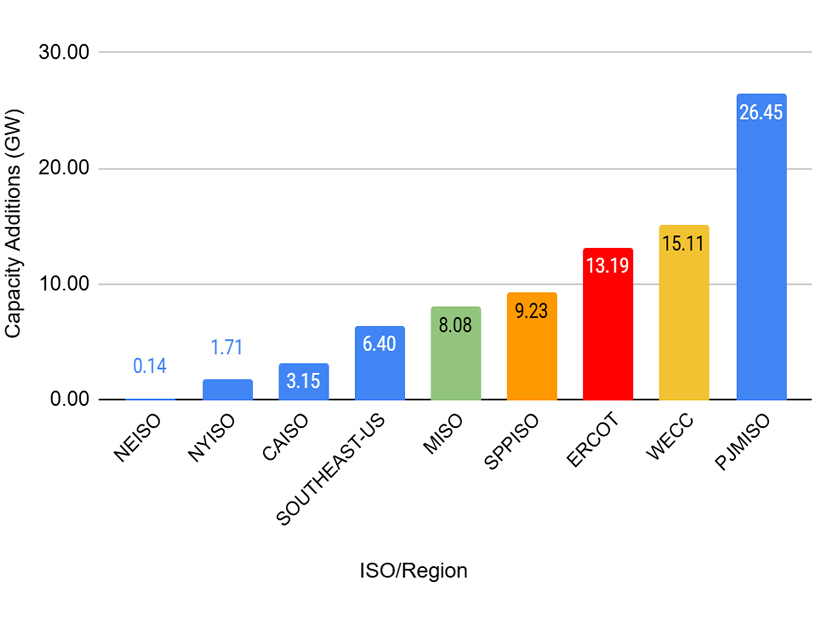

Load center capacity additions from 2020-2025 | Yes Energy using Yes Energy’s Infrastructure Insights data

Oct 20, 2025

|

Data center-fueled demand growth continues to soar while reserve margins continue to shrink. Meanwhile, the timelines for building load versus building generation and transmission are wildly out of sync.