Mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM has had a rough couple of weeks. On July 16, it received an open letter penned by nine bipartisan governors of the 13-state region it serves, citing a “crisis of confidence from market participants, consumers and the states.” Admonishing PJM for its “multiyear inability to efficiently connect new resources to its grid and engage in long-term transmission planning,” the governors called for fundamental changes and new leadership.

From Bad to Worse: The July Capacity Auction. That was bad enough. But then things got worse, with the release of record high results from the Base Residual Auction for capacity addressing the 2026/27 delivery year.

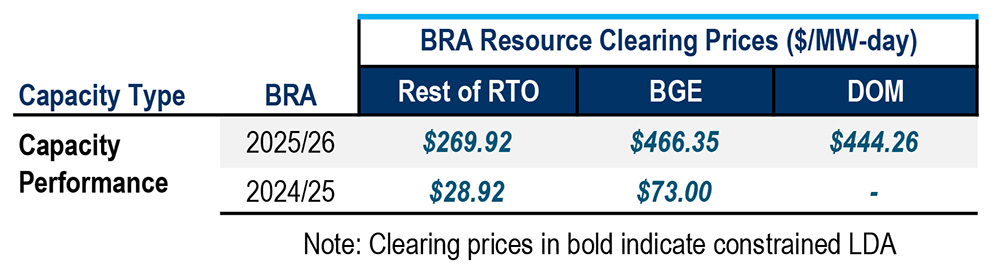

Last year’s auction results already had caused an uproar, as the clearing price for most of PJM was set at $269.92/MW-day, up dramatically from $28.92/MW-day the prior year. Baltimore Gas and Electric and Dominion fared even worse, at $466.35/MW-day and $444.26/MW-day. Total costs paid for capacity by all energy consumers soared from $2.2 billion to $14.7 billion in just one year.

Comparison of BRA clearing prices by delivery year by LDA | PJM

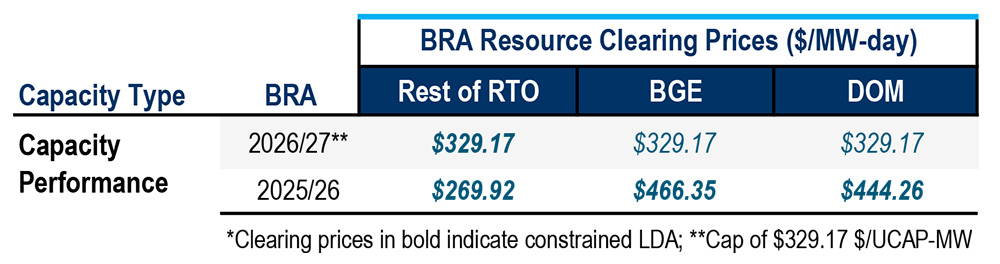

In response and in an attempt to limit future costs to customers, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro (D) negotiated a floor and cap with PJM — eventually blessed by FERC — that would create a price band between $177.24/MW-day and $329.17/MW-day for the following two delivery years. (See FERC Approves PJM-Pa. Agreement on Capacity Price Cap, Floor.)

Many feared the July 2025 auction would hit the new cap, and it did just that, pegging out in all delivery zones at the same price (good news only for BG&E and Dominion) of $329.17/MW-day. Total estimated cost to load increased as well, from $14.7 billion to $16.1 billion. (See PJM Capacity Prices Hit $329/MW-day Price Cap.)

Without the cap, it could have been worse. PJM noted in its BRA report that an uncapped simulated auction likely would have cleared at over $388/MW-day. Capacity prices now may be costing customers up to 25% or more of their total bill, raising the questions, “How did we get here?” and “What does this imply for future energy costs?”

The answers to those questions are not simple (though some politicians will try to paint them that way), but they generally come down to the balance between expected supply and forecasted demand.

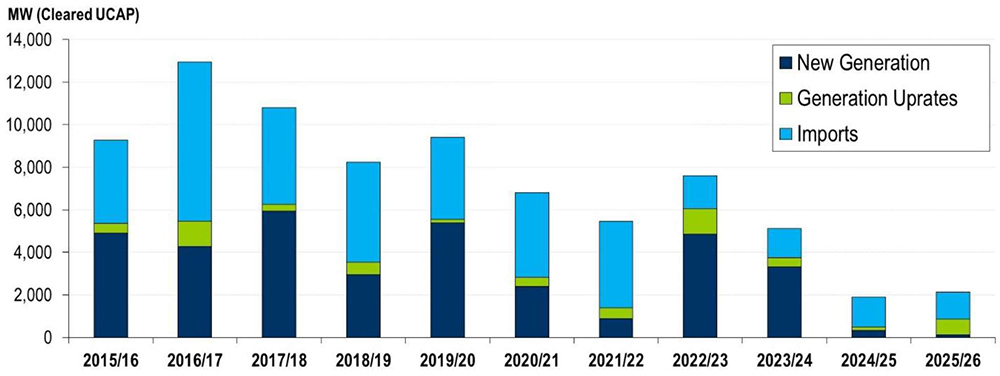

Supply: An Increasingly Bleak Scenario. Among major issues affecting supply, in 2024 PJM revised the way it accredited generation resources for their ability to provide capacity during critical peak periods. Nearly every type of resource in PJM’s portfolio took a significant hit.

For example, every nameplate MW of gas combined-cycle capacity was reduced from 96% to 79%, while that for simple-cycle peakers fell from 90% to 62%. Solar and storage capacity contributions also were revised downward considerably, and even nuclear and coal units were de-rated (from 99% to 95% and from 88% to 75%, respectively). Meanwhile, little additional capacity has been added to the grid recently, with much of that from renewables. Add to that the retirement of several coal units, and dispatchable supply capacity has not kept pace with demand.

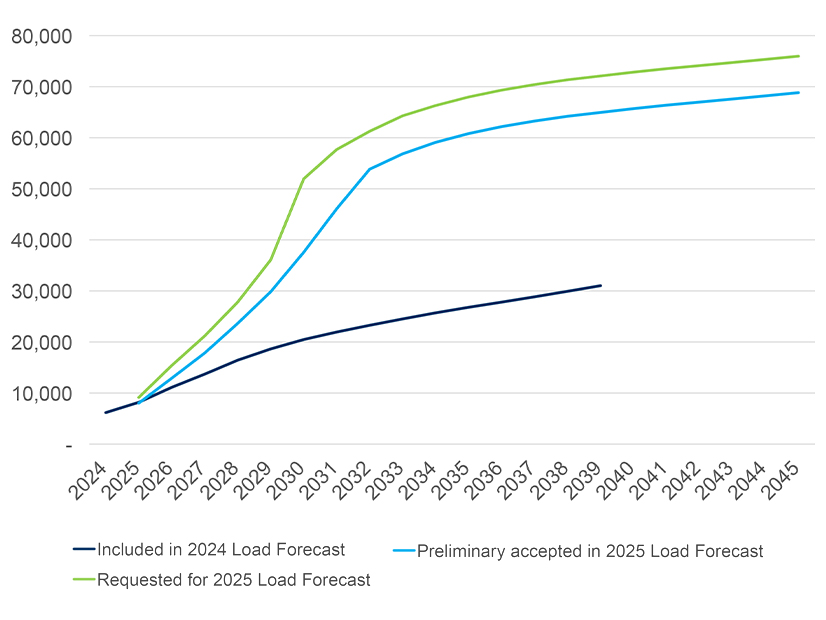

Forecasted Rapid Demand Growth: An Unexpected Surprise. The perfect recipe for creating more pricing pressure when supply is limited is to add large amounts of potential new demand, and the addition of data center load does just that. These facilities are large (often well over 100 MW), disconnected from the general macroeconomic environment, and extraordinarily difficult to forecast, especially when the majority of current interconnection requests to utilities may never actually be served with power. Existing and forecasted data center load clearly had the potential for a significant impact on the past two auction results. The question is, how much?

In fact, it likely may have resulted in billions of dollars of unnecessary costs to consumers. PJM’s Independent Market Monitor (IMM) ran alternative scenarios earlier this year to evaluate this issue and concluded, “data center load growth is the primary reason for recent and expected capacity market conditions, including total forecast load growth, the tight supply and demand balance, and high prices.”

The IMM attributed $9.3 billion of the $14.7 billion from last year’s auction to data centers, noting, “the inclusion of forecasted data center load increased total revenues by $7,742,157 or 115 percent.” (emphasis added). The IMM further commented, “the role of data center load does not mean that PJM would not have eventually reached a point where supply and demand were tight, but that trajectory was relatively slow and would have resulted in more time to permit market reactions to address the balance of supply and demand.”

Phantom loads and poor forecasting are likely to create a political firestorm. What the IMM report implies is that if that forecasted future data load is incorrect, then everybody else ends up paying for a mirage that does not exist. That leads immediately to the more obvious multibillion-dollar question: “How accurate is PJM at forecasting data center loads?”

An analysis of how PJM arrives at its forecast is not very comforting. The grid operator arrives at its number by taking very imprecise utility forecasts that are based on interconnection requests from data center developers and speculators who buy land and place interconnection requests with the eventual goal of selling the projects.

Both types of entities place multiple applications with utilities in multiple states. Their behavior is similar to that of generation asset developers prior to FERC Order 2023 (which required them to put more financial skin in the game, with required deposits and penalties for withdrawing from interconnection queues).

Many developers placed multiple chips on the board, knowing that if one project succeeded, they eventually would withdraw the others. This resulted in highly inflationary supply numbers. In fact, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory’s 2024 analysis of interconnection delays reported that for supply assets seeking interconnection between 2000 and 2018, only 19% actually flowed power by the end of 2023.

The data center dynamic is similar enough that some lawmakers and regulators are catching on. For example, recently passed Texas legislation SB 6 requires developers of large loads to disclose whether they are seeking similar requests for service elsewhere in Texas (note, that’s only in Texas).

It’s difficult to say how much inflated load actually exists, but one report characterizes this approach of developing multiple requests as a “low barrier, low cost, low risk strategy” employed by developers to access power wherever they can get it. That report also quoted a former Google senior director as saying the numbers could result in “five to 10 times more interconnection requests than data centers actually being built.”

Despite this inflationary dynamic, PJM’s 2025 large load forecast only minimally reduced the numbers supplied to it by the utilities in its service territory. While the problem already shows up in the capacity auctions for 2025/26 and 2026/27, this lack of rigor gets worse in the out years when projected data center growth skyrockets.

Not surprisingly, some consumers are worried, especially the more sophisticated and large users with the most to lose. A May 30 open letter to FERC from a number of large industrial groups urges the commission to “initiate an independent examination of current load forecasting practices and potential improvements to those practices.” That letter cites “the uncertainty and lack of transparency surrounding current load forecasting practices across the country,” and the impact it can have on costs.

What’s Next? The latest auction signals tough sledding for consumers, with little end in sight. Given the magnitude of the costs related to potentially inaccurate demand forecasts, combined with the red-hot politics surrounding the global race to dominate artificial intelligence, it’s not hard to imagine PJM’s capacity auction results becoming intensely and increasingly politicized.

The action to address this issue is to employ far more rigor in the forecasting process at the utility level (while ensuring that each utility uses similar processes) and employ a higher level of rigor within PJM’s forecasting approach. The second is to do everything possible to accelerate deployment of new capacity in the system.

However, with the next auction less than six months away, don’t expect the cavalry to arrive anytime soon. They haven’t even saddled up their horses.

Around the Corner columnist Peter Kelly-Detwiler of NorthBridge Energy Partners is an industry expert in the complex interaction between power markets and evolving technologies on both sides of the meter.