Floods have been top of mind in 2025, mainly because of the tragic Central Texas flash flood, which took more than 130 lives over the July 4 weekend. The Texas disaster came less than a year after Hurricane Helene dumped more than 20 inches of rain far inland, causing massive floods that caught residents off guard and destroyed areas in the Carolinas, Tennessee and Virginia.

For grid operators, power generators and utilities, the rise in extreme rain events causes immediate damage and requires long-term planning to minimize future damage.

This is the second in a series on how climate extremes are impacting the grid; the first looked at how extreme heat impacts the full length of the electric supply chain.

It’s Raining, It’s Pouring

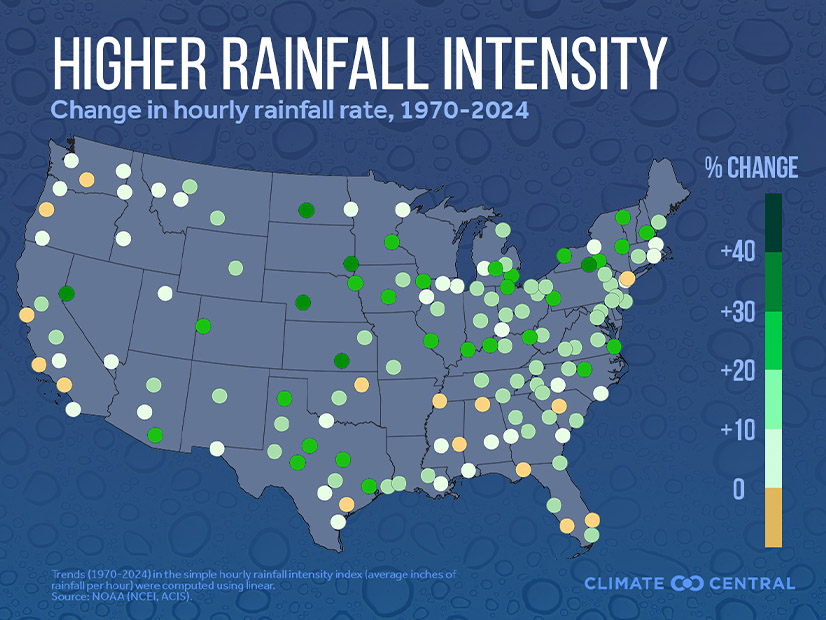

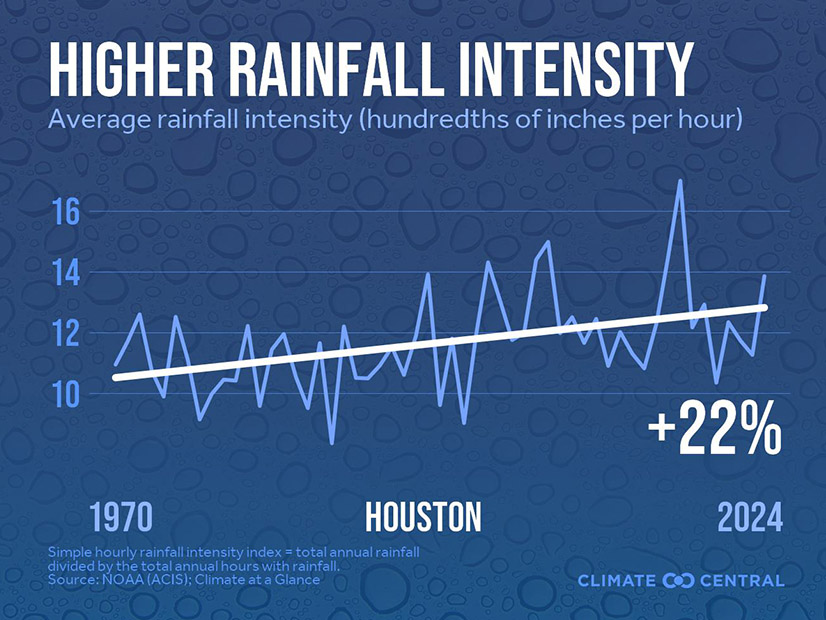

If you think you are hearing about heavier rain events more often, it’s because you are. Most areas of the United States are experiencing heavier rainfall, according to Climate Central. Earlier in 2025, four 1-in-1,000-year rain events hit Texas, North Carolina, New Mexico and Illinois.

By the end of July, 2025 had broken records for the most flash flood warnings issued by the National Weather Service in the first seven months of a year, with nearly 4,000 issued. Most flash floods occur between May and September each year when the warmer atmosphere carries more moisture and the drier soil is unable to absorb the rain.

Like many flash floods, the Texas floods this year were caused by a tropical storm or hurricane: the remnants of Tropical Storm Barry. There have been deadlier flash floods in the United States, but the Texas event had the highest flash flood death toll in nearly 50 years. While cell phone alerts and real-time tracking usually enable faster reaction to rapidly evolving weather events, the Texas storm became a disaster in part because of failure to send timely warnings, incompatible first responder communication systems and inadequate local emergency manager training.

Flash floods aren’t the only type of flood that impact the grid: river floods and storm surge floods also are dangerous, but without the surprise factor. They also tend to have fewer fatalities, and without the rapidly moving debris carried by the water, property damage differs. Sunny-day flooding, when high tides inundate seaside neighborhoods, will be explored in a future column on sea-level rise.

La Niña, Meet Bombogenesis

As extreme precipitation events have become more common, colorful meteorological terms have crept their way into the lexicon. Even if you don’t understand the nuances, there’s a good chance you’ve added derechos, microbursts, atmospheric rivers and bomb cyclones to the long list of more common wet weather events you grew up with: thunderstorms, tropical storms, hurricanes and La Niña, which officially has arrived.

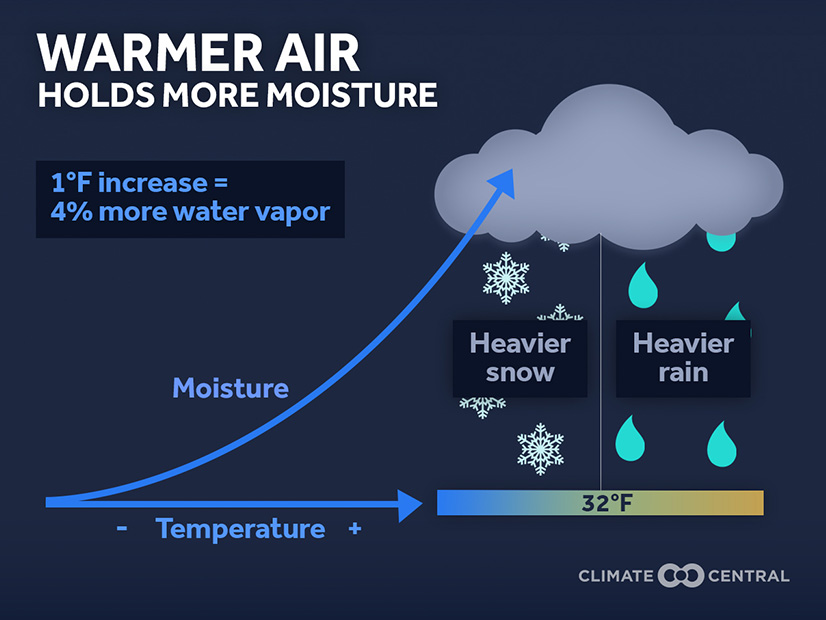

They are all variations of the water cycle we all drew in elementary school, and all are getting worse and more common for the same reason. Climate change causes more extreme precipitation events: for every degree Fahrenheit the atmosphere is warmer, it holds 4% more moisture. So when, say, a hurricane forms over the Gulf during a marine heat wave, it will carry significantly more water than if it had formed in normal temperatures, and that extra moisture means heavier rains along the path of the storm.

Sometimes, extreme precipitation arrives as a solid, not a liquid. Hail is formed when updrafts push raindrops into freezing areas of the atmosphere where they collide and join. If the trip down to earth isn’t warm enough, they hit, still frozen. Hailstone size is determined by the speed of the updraft: A 60-mph updraft can create walnut-sized hail, while a 100-mph updraft can produce grapefruit-sized hail, large enough to kill someone.

Extreme weather doesn’t happen only on the hotter side of the temperature scale. While hailstorms are more likely in spring and summer, in winter, there are risks of heavier snow or ice storms, which can take down power lines and make it challenging for repair crews to reach the damaged lines. In fact, winter is the fastest-warming season of the year, meaning more moisture in winter storms as well.

Mapping the Wetter Climate Future

The Texas Hill Country is known as flash flood alley due to the mix of topography and soil types that can lead to heavy rainfall moving quickly into gullies and gaining speed. Sophisticated software can model where and how fast water will flow, but as climate change increases the frequency and severity of events, meteorological and climate science professionals need up-to-date data to better predict the impact of storms. Without it, emergency services and utility crews will have less chance to prepare for storms.

Even with great models, damage from extreme rain can be larger than predicted, such as when a hurricane stalls like 2017’s Hurricane Harvey that dumped 60 inches of rain on Nederland, Texas, 90 miles east of Houston, or when one detours further inland like Hurricane Helene.

In First Street’s report on extreme precipitation, its climate data team said the past precipitation maps from NOAA are losing relevance as they were generated with inconsistent time periods and do not reflect the most recent and relevant rainfall data. The NOAA Atlas 15 map of precipitation risk, intended to address the problems in old maps, was at risk of being shelved during recent budget cuts. However, funding for the project was reinstated after the devastating floods in Texas. For utilities and grid asset owners, the National Water Prediction Service’s Flood Inundation Mapping tool offers planning teams insight into where they are most at risk.

The Perfect Storm of Storms

Floods cause more deaths than any other type of natural disaster. Residents, first responders and utility crews face immediate danger from rising or fast-moving water; downed wires or inundated underground systems add the potential for electrocution. Outages of power, communication and traffic systems exacerbate these risks. And once the rain stops, they all face the (sometimes lengthy) task of living with damaged infrastructure while it’s being rebuilt.

In terms of the grid, the distribution network is most at risk of poles and wires being taken down by falling trees or fast-moving debris. Where heavy rains follow a fire, mudslides up the ante.

“A debris flow is like a flood on steroids,” Jason Kean, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey told the New York Times after the Palisades and Altadena fires in Southern California earlier in 2025. “It’s all bulked up with rocks and mud and trees.”

The transmission system is more likely to be harmed by extreme weather events that include high winds, but even without winds, fast-moving water can erode pylon foundations and inundate underground assets. A 2019 report by Oak Ridge National Laboratory noted: “Water from inundation or flooding may follow electrical lines back to underground conduits and vaults, damaging underground substations.”

The power generation system is at risk as well. Power plants are at risk of flooding, the Oak Ridge report said, “a consequence of the need for most thermoelectric plants to be close to sources of cooling water,” though there is little research quantifying it. After Hurricane Harvey, ERCOT said about 7,500 MW of generation capacity was out of service, with other units operating at reduced capacity. And Texas’s 2021 disastrous deep freeze showed how vulnerable the gas generation system was to extreme cold.

Hydro generation — which you would expect to benefit from more precipitation — is vulnerable if dam levels aren’t properly managed during a flood. Michigan’s Edenville Dam, which was built in the 1920s for hydroelectricity but had its license revoked by FERC in 2018 due to safety issues, failed in a 2020 flood, which overwhelmed its mile-long embankment.

Hail can damage grid assets such as solar farms, though solar panels are designed to handle a significant impact. At a SolarWorld event in 2015, I shot panels with a hail gun that sent ice pellets at 50 miles an hour, and the modules were unscratched. But I’ve also seen images of acres of broken panels following severe hail. Today, solar farms with trackers that tilt the modules to face the sun have software that uses hyper-local weather data to know when a hailstorm is approaching and stow panels vertically to minimize damage.

All for One, and One for All

As the prevalence and severity of extreme weather events rises, utilities’ ability to respond quickly and effectively will become even more critical. Part of that response is ensuring coordination with first responders and utilities in neighboring areas.

Utilities help each other out when disasters strike, often crossing state borders and staging ahead of a storm. The mutual assistance networks, coordinated by groups like the Edison Electric Institute and the American Public Power Association, speed up recovery. But as extreme weather events become more common, we’re more likely to run into challenges where crews will be too busy in their own area to help out nearby.

The cost of climate disasters also comes into play. Earlier in 2025, the firefighters union in Austin, Texas, voted no confidence in the city’s fire chief for withholding participation in the mutual aid effort following the Kerrville floods. He claimed the city budget meant they could not afford to support the neighboring area in its time of need.

Building Resilience for a Wetter Future

For utilities, grid owners and operators, planning for a wetter future requires hardening the physical infrastructure and readying other resources.

For the physical infrastructure, what seems over-engineered today may be just right in a future where larger and more common floods may erode foundations, and debris may try to take power poles with it. And before undergrounding wires, transformers and substations — an oft-requested upgrade in fire-prone areas and high-end developments — check those all-important precipitation and inundation maps to understand the potential for those assets to be inundated the next time extreme rain hits.

It is easy to understand why utilities are stockpiling key components to make future rebuilding easier, even though it may exacerbate shortages nationwide. The industry already is facing shortages and extended lead times for transformers, distribution poles and substation equipment. Tariffs have exacerbated the issue, as 80% of transformers, for example, are imported.

As far as human resources go, mutual assistance networks will be critical as neighboring utilities call on each other to respond to a rising number of floods and other extreme weather events. And utilities and asset owners will need to build larger contingencies in their budgets for the extra overtime and asset replacement that goes along with that response.

Power Play Columnist Dej Knuckey is a climate and energy writer with decades of industry experience.