As you know, Westinghouse, its two (Canadian) owners, and the U.S. government announced plans for $80 billion of investment in new nuclear plants. Recent articles are here, here and here.

I’ve been skeptical about new nuclear for many years — whether it be microreactors for U.S. military bases, new nuclear generally, small modular reactors in Ontario, nuclear fusion or Vogtle, as I wrote about here and here. And the skeptic’s case remains powerful.

But a recent study from DOE’s Idaho National Laboratory (INL) leads me to think this recent announcement could be a vehicle for something important. Maybe very important.

The NOAK Unit

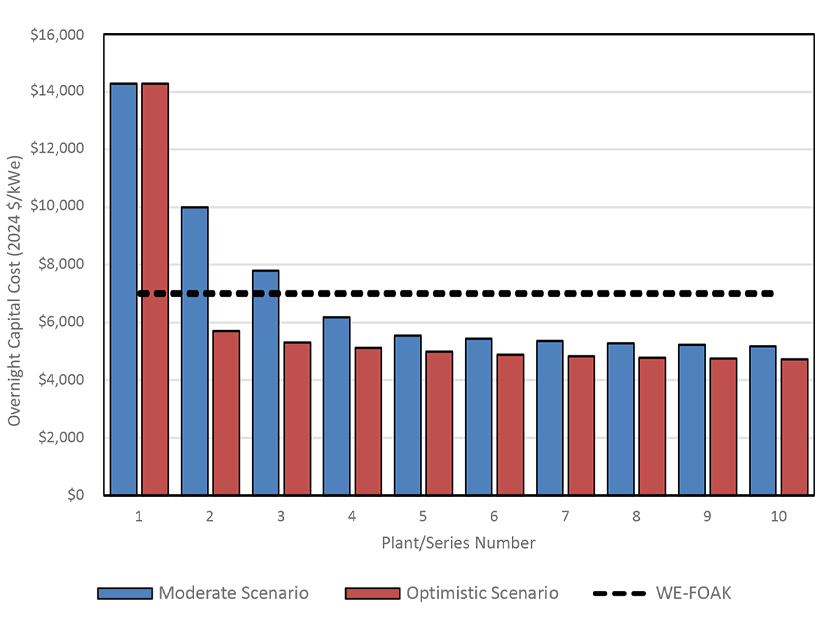

The INL study makes a strong case that the cost of new nuclear plants could decline from the Vogtle experience as multiple units are constructed, until reaching a “mature” (“nth of a kind” or NOAK) cost of around $6,000/kW at around the seventh to ninth plant. The projected cost reduction from Vogtle’s $15,000/kW? About 60%. The chart from the study (see above) illustrates the cost reduction in terms of capital cost per kilowatt (a “series” is two plants).

You can read the study for the various drivers of the cost reduction.

The China Experience

The INL study bases much of its analysis on China achieving low and declining costs and construction times with its past completion of four AP1000 (Westinghouse design) units, and its 11 CAP1000 and CAP1400 units (adapted from the Westinghouse AP1000 design) now under construction, as listed here.

A separate Harvard study is featured in a recent New York Times article, with more color here. A chart shows capital costs for new Chinese projects under construction at around $2,000/kW.

This Chinese capital cost is about one-third of what the INL study says is possible in the U.S. This would suggest that the INL NOAK cost is not just whistling Dixie.

Cost of New Nuclear Versus Alternatives

So what would the INL NOAK cost mean relative to the costs of other electric power generation?

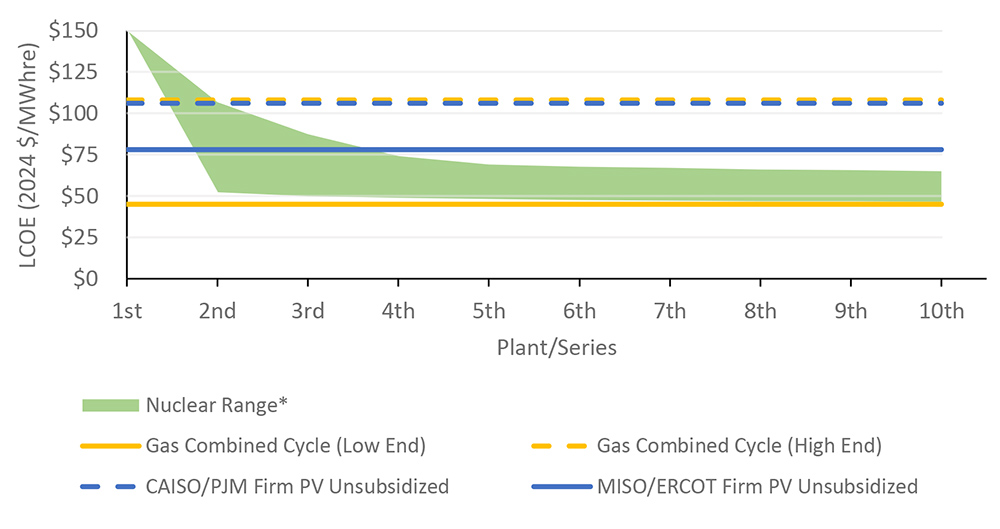

Here’s a chart from the INL study showing the anticipated U.S. cost reduction in $/MWh Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) terms in the context of other generation costs.

The nuclear range is shown with and without an investment tax credit (ITC). You’ll see that with or without an ITC, nuclear costs start falling below firmed-up solar (based on Lazard estimates) after several nuclear units. And new nuclear cost falls within the broad range for new gas combined cycle cost (not to be confused with the very low cost of retaining existing gas units, even with carbon emission mitigation, as I’ve discussed before).

Importantly, these LCOE cost comparisons are before consideration of the social cost of carbon. If a social cost of carbon were incorporated, such as the $66/tCO2 discussed here, with a $/MWh equivalent of about $30/MWh, the above combined cycle costs would go up substantially. Another way of looking at it is to consider the social cost of carbon as roughly similar to the ITC financial benefit, so the social cost of carbon is rough justice supporting the ITC as an economically justified subsidy.

Location, Location, Location

The prior chart illustrates another important consideration. You’ll note that firmed-up solar in MISO and ERCOT has an LCOE about $30/MWh less than firmed-up solar in CAISO and PJM. This illustrates Lazard’s detailed analysis of the costs of firming up solar and wind, finding that LCOEs differ dramatically by region and by resource.

Given that solar and wind are much more expensive in some regions than in other regions, are the high-cost regions going to decarbonize if it means a permanent economic disadvantage? The only fix (absent nuclear) would be very expensive, difficult-to-site transmission to move power from low-cost renewable regions to high-cost renewable regions.

Nuclear is not location dependent. That could be important for high-cost renewable regions to reduce carbon emissions at competitive cost.

Getting There from Here

So new nuclear might be competitive, but here’s the rub: Who’s going to put up $14,000/kW for the first two units? Or $10,000/kW for the next two? Absent taxpayer (or tech bro or foreign country) financial support, new nuclear can’t get out of the starting gate.

We should recall that taxpayers footed the bill to get solar and wind going, starting almost 50 years with an ITC. EIA estimates that between 2016 and 2022, renewables received $84 billion in federal taxpayer support, while nuclear received $3 billion over the same period.

Assuming the INL capital costs, we can ballpark what it would take in taxpayer subsidies to buy down the cost of the first six nuclear units to the projected cost of the seventh unit (which yields an LCOE below firmed-up solar). Taking the cost differences and applying the 6,600 MW of six AP1000 units comes to $30.8 billion.

Taxpayer funds could be provided over time to match a schedule for outlays. The first two to three pre-construction years for a given plant wouldn’t require much money, but they would get the ball rolling.

An Elephant in the Room

Let me acknowledge a structural weakness in this plan: the creation of a monopolist, Westinghouse. Monopolies by nature raise prices and have limited incentive to be efficient, with poster child Vogtle as I’ve written before here and here.

But the situation here might be the exception to the rule if potential profits from future NOAK units, assuming price targets were achieved, were sufficient incentive for Westinghouse and its major vendors to contain costs on the subsidized first units. And the actual agreement could have financial features designed to incent cost containment.

The Actual Agreement

Regarding the actual agreement for the new initiative, one of Westinghouse’s owners said it expects it to be done around the end of the year.

The details of such an agreement are critical to any chance of success. Who’s doing what, when, how and where? What are the incentives to do what, when, how and where? Who’s qualified to do what, when, how and where? Who’s bearing the cost overrun and schedule delay risks of what, when, how and where? Who’s independently monitoring what, when, how and where? What are the enforcement measures to ensure everyone does what they commit to do, when, how and where?

If the requisite engineering, finance, economic, commercial and legal expertise for such an agreement doesn’t exist in the U.S. government, hire it from outside. There’s too much at stake to wing it.

Bottom Line

There are three established sources of carbon-free electricity: solar, wind and nuclear (putting aside hydro with its limited expansion prospects). With staggering need for more electricity, are we going to give up on one of the three — the only one that is not intermittent and not locational? As Wayne Gretzky (actually his father) said: “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

Let’s take a shot, America.

P.S. For the holiday season in these challenging times, here are some lists of happy music courtesy of some good folks on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. And here’s a classic video for the season by the Dropkick Murphys. The best of the holidays to you and yours!