The grid was never designed for the world it’s being asked to serve. Electrification is accelerating faster than planners expected; extreme heat is swelling peak demand; and climate-driven disasters are smashing records while breaking infrastructure.

Yet the electric industry is expected to build a grid that can deliver reliable power to regions that may succumb to, survive or even thrive in a future further affected by climate change.

Planning for the grid of the future requires increasingly sophisticated prognostication, and the industry needs to look to new data sources for modeling. Climate scientists and economists have become as important as engineers, and traditional peak-demand forecasts and resource-adequacy models cannot capture the compound stresses facing today’s grid.

Wayne Gretzky famously said he “skate[s] to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.” That’s all very well if you know where it’s going to be — difficult for a puck, even more so for a grid being expanded in an environment some call a polycrisis.

Utilities and regional planners no longer can rely on models built for a more stable, predictable climate, one that no longer exists. To build a grid that is both reliable and resilient, planners now need modeling tools that integrate growth patterns and climate risk. The next generation of modeling — probabilistic, scenario-based, climate-informed — is not simply an upgrade. It’s becoming the minimum requirement for any utility, regulator or investor hoping to keep pace with the world in which the grid must operate.

A new measure launched in November by the First Street Foundation may prove a critical tool for understanding the intersection of climate risk and economic growth.

Understanding Resilience Spread

Resilience Spread, a concept coined by First Street, captures the intersection of two opposing forces, like Dr. Doolittle’s fictitious Pushmi-Pullyu, a double-headed llama that tries to move in two opposite directions at once. In one direction, there are positive market forces, reflected in population growth, economic strength and amenities such as housing and transportation. In the other direction, there are negative climate risks.

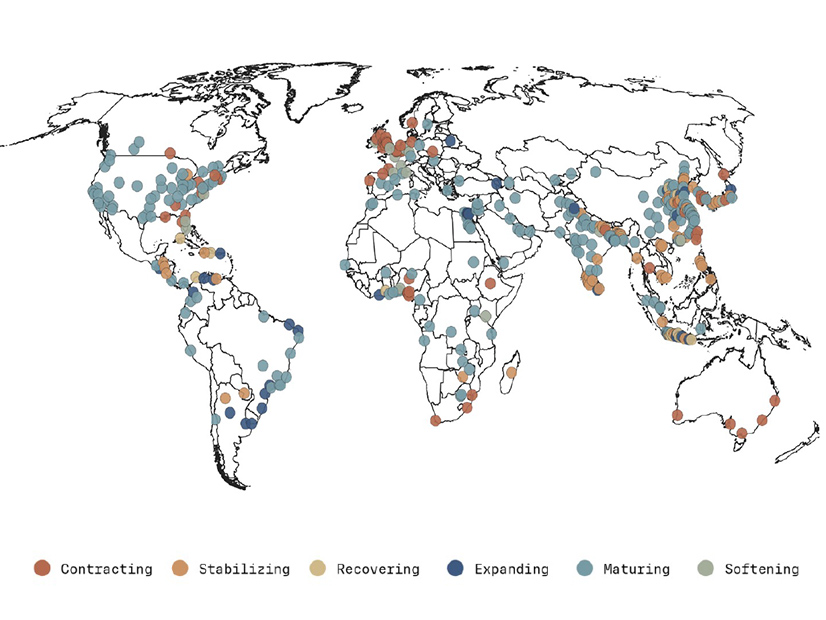

The Resilience Spread quantifies the gap between a region’s climate exposure and its ability to adapt. It’s a gap that is widening in many areas, creating a patchwork of vulnerability. Looking at 400+ of the world’s major cities, First Street determined that economic strength is outweighing climate risk by a massive $1.8 trillion globally, which “illustrates that, on average, strong macroeconomic conditions and consumer confidence continue to offset the drag of climate hazards,” the report said.

But the average is meaningless for planners. What’s important is how individual cities are expected to perform, and that ranges widely. And there’s also the factor of time. While today’s global spread is net positive, “this cushion is not permanent. Without significant adaptation, the spread is projected to erode steadily, tipping negative before the end of the century as climate pressures intensify faster than foundational macroeconomic conditions.”

The speed at which we lose the economic buffer depends on how we invest in adaptation. The firm predicts that unless those investments are substantial, the global spread will be eroded fully by 2085, “as intensifying hazards outpace resilience.”

The Many Faces of Climate Risk

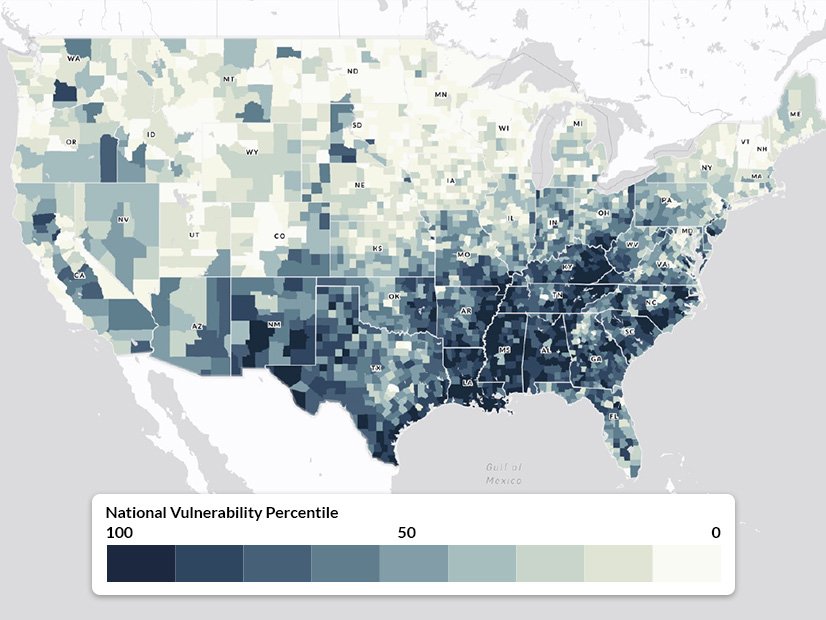

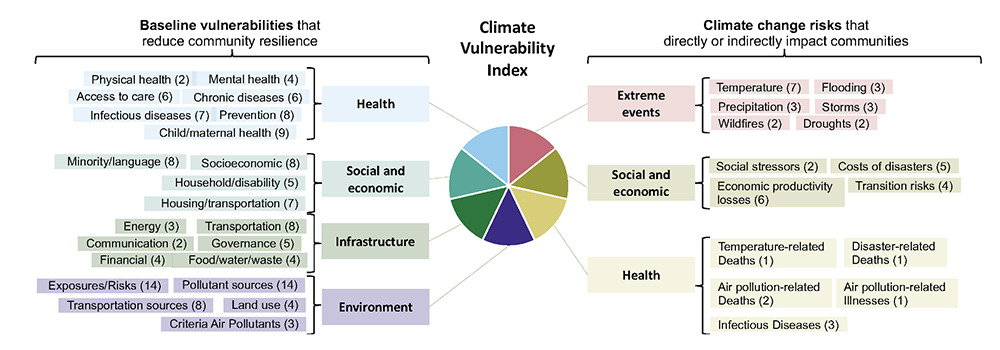

Climate risk comes in many flavors. The U.S. Climate Vulnerability Index map, developed by the Environmental Defense Fund and Texas A&M University, drills down on the various climate risks and impacts in each county or census tract. It maps extreme events, such as storms and droughts (see our series on the effects of extreme climate events on the grid: fire, flood and heat), as well as impacts such as heat-related deaths and other factors such as air pollution and socioeconomic stressors.

The index accounts for an essential piece of the resilience equation: If an area already is struggling, it is less likely to withstand the challenges posed by climate change.

First Street distinguishes between chronic and acute risks: “Chronic risks reflect long-term, gradually intensifying physical climate stressors such as heat, drought or sea level rise, while acute risks capture short-term, high-intensity events like floods, storms or wildfires.”

For grid planners, chronic risks are easier to plan for, and the grid can be hardened to resist them in advance, but acute risks are more likely to damage significant portions of the grid, providing the opportunity to rebuild in a more resilient way.

Growth in All the Wrong Places

Why, in a world where we’ve known for a few decades that climate change will adversely affect major economic centers on the coasts, are some of the biggest economic centers also the most at risk of climate damage? Because many of the biggest cities were located at trading hubs, which historically were at deep ports. First Street found what it called a “striking paradox.” Of more than 400 major global cities, “over half of global urban GDP is concentrated in places facing the highest levels of acute climate risk.”

A city’s attractiveness as a place to live and do business can survive high climate risk, according to First Street. “Many of the world’s most economically productive cities remain hubs of growth despite sitting in the top quartile of acute risk.”

Miami is an example of a city that is both one of the world’s most productive, high-growth cities and among the most exposed to climate events, such as sea-level rise, heatwaves and hurricanes. Despite being in the top percentile of climate risk, its economic strength is buoyed by amenities ranging from a strong labor market to the desirability of living near wide sand beaches.

In cities like Miami, where the market effect outweighs the climate effect, First Street’s resilience spread is positive.

“These positive spreads imply that markets potentially undervalue their opportunities relative to climate risk, highlighting a hidden upside, as capital inflows remain strong and long-term attractiveness endures.” For planners, that resilience spread can be used as a factor to adjust growth models upwards.

They also caution that the spread today is looking forward from one point in time. “Resilience is not fixed. Cities that thrive today may falter tomorrow if climate risks intensify … and begin to outpace the economic foundations that support their growth.”

When the Resilience Spread is Negative

On the other end of the spectrum, a negative resilience spread occurs when the negative climate effect exceeds the positive market effect. “Climate risks’ impact on location desirability already outweighs local economic strengths in roughly 30% of global cities today,” First Street found.

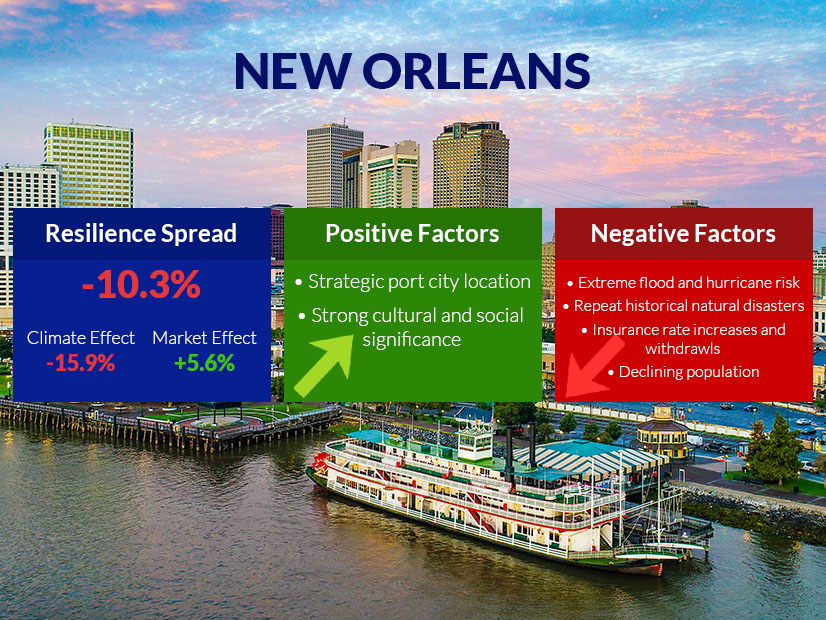

New Orleans is an example where its role as a strategic port and its cultural significance fail to counterbalance the impact of its exposure to acute climate risks, most notably hurricanes and the resulting flooding.

Repeated extreme storms, including Hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Ida in 2021, “have driven steady population decline, unaffordable insurance rates and insurer withdrawal, resulting in a deep negative resilience spread of -10.3%,” First Street said.

For cities such as New Orleans, grid planners face a difficult calculation: how much to invest in the grid’s resilience where climate threats are substantial and population is declining.

There is a risk that a deep understanding of climate risk modeling will lead to inequity. When there are so many competing capital investment demands, it can be tempting to deprioritize regions with weak adaptive capacity where any investments face greater risks from climate damage or economic decline. Yet those areas may depend most on investments today to withstand future challenges. Until there are discussions about managed retreat from the most climate-vulnerable areas — a topic few political leaders are willing to touch — policies must support the vulnerable communities as well as the well-resourced areas.

System Strength and the AI Demand Growth Wild Card

The market effect and climate effect are just two of the plethora of factors that planners need to consider. Infrastructure fragility — the ability of each part of the grid to withstand acute and chronic climate risks — is another key variable that will be the topic of a future column. And population trends also are key in a time of increased climate migration.

Perhaps the largest factor outside of climate change that is complicating grid planning is the rise of data centers, especially AI data centers, which weren’t foreseen only a decade ago. It has moved forecasts that had been flat to negative into positive territory. S&P Global Commodity Insights anticipates U.S. electricity consumption “to grow at a compound annual growth rate of more than 3% from 2025 to 2030, with generation in tow.”

That demand is not spread evenly throughout the country but is lumpy with intense localized demand in the areas where they are being built. Northern Virginia is the poster child for unexpected load growth, with 70% of global internet traffic carried by the more than 200 data centers in the county, according to Oxford American. As RTO Insider columnist Peter Kelly-Detwiler pointed out recently: “These facilities are large (often well over 100 MW), disconnected from the general macroeconomic environment and extraordinarily difficult to forecast.”

Investing in Foresight

With so many competing factors shaping the grid of the future, utilities, ISOs and regional planning entities will need to invest in data infrastructure and modeling capabilities, building internal capabilities and accessing external expertise as needed. A key part of this will be ensuring acute and chronic climate risks are understood and accounted for, both in cities and rural areas, and in high-risk and high-growth areas.

The competing forces of market strength and climate vulnerability vary within any territory served by each utility, grid operator or policy body, and there’s no single approach to planning that serves communities at opposite ends of the resilience scale. But all areas will be served better by industry and policy leaders who insist on, and invest in, advanced modeling.

Without smart, sophisticated modeling, planners will be flying blind—and costs, blackouts or inequities will be the price.

Power Play columnist Dej Knuckey is a climate and energy writer with decades of industry experience.