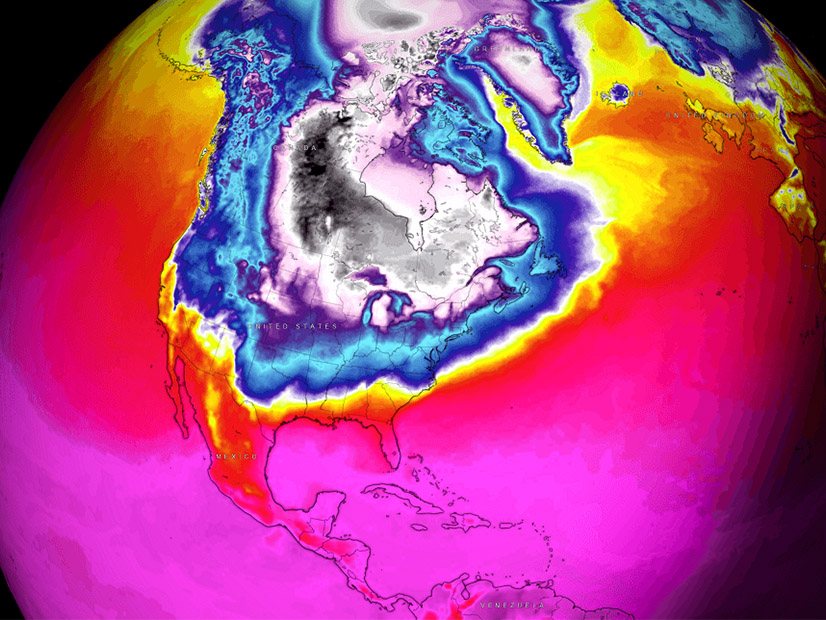

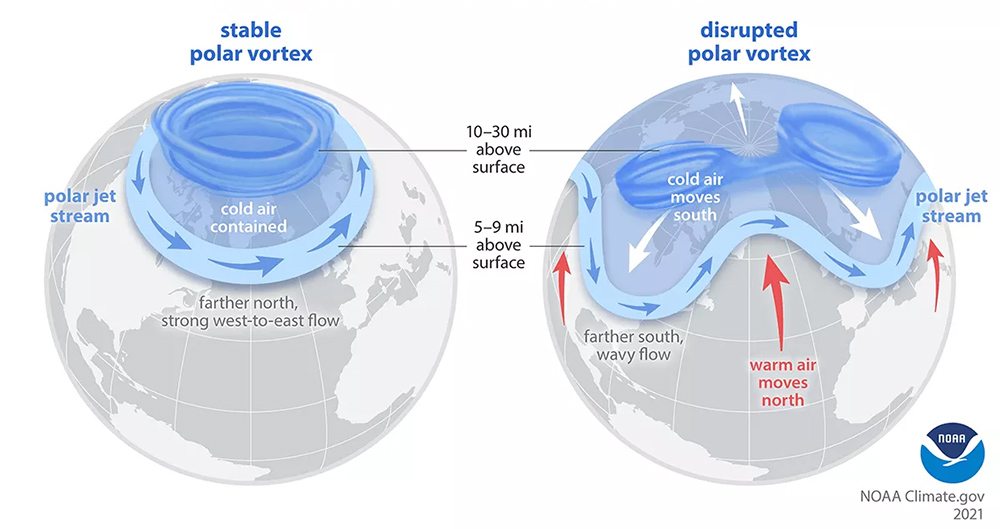

In late January, the mass of cold air — typically held at bay by the high-level upper atmosphere winds that occur 10-30 miles above the North Pole — staged a jailbreak. A breakdown of the polar vortex occurs every so often when sudden stratospheric warming occurs (that’s what occurred during 2021’s devastating Winter Storm Uri), disrupting the vortex and allowing fugitive cold air to spill southwards, bringing extremely cold temperatures in its path. Collision with low-pressure systems can create a volatile cocktail of ice and snow.

That’s exactly what happened when the much-anticipated Winter Storm Fern swept across the country at the end of January. The southeastern U.S. suffered the brunt of physical damage, as high-level warmth brought rain that froze as it encountered cold air close to the ground, coating power lines with ice, breaking equipment and leaving approximately 1 million people without power.

Most damage came from ice on distribution networks, with Entergy estimating 860 poles and 60 substations out of service. Some larger transmission lines also were affected. Entergy reported 30 transmission lines out, and the Tennessee Valley Authority also saw as many as two dozen high-voltage transmission lines affected.

While thousands of customers went without power for many days, and the damage to the distribution system was serious, the bulk power system in the southeastern U.S. generally held its ground. The same was true for other regions of the country that got mostly snow but saw extreme cold prevail from Texas to New England.

This stands in stark contrast with winter storms Uri (February 2021 — with its extended system-wide outages in Texas) and Elliott (December 2022 — with outages in TVA and Duke service territories, while PJM barely squeaked by).

Thermal Plants, the Winter Workhorse

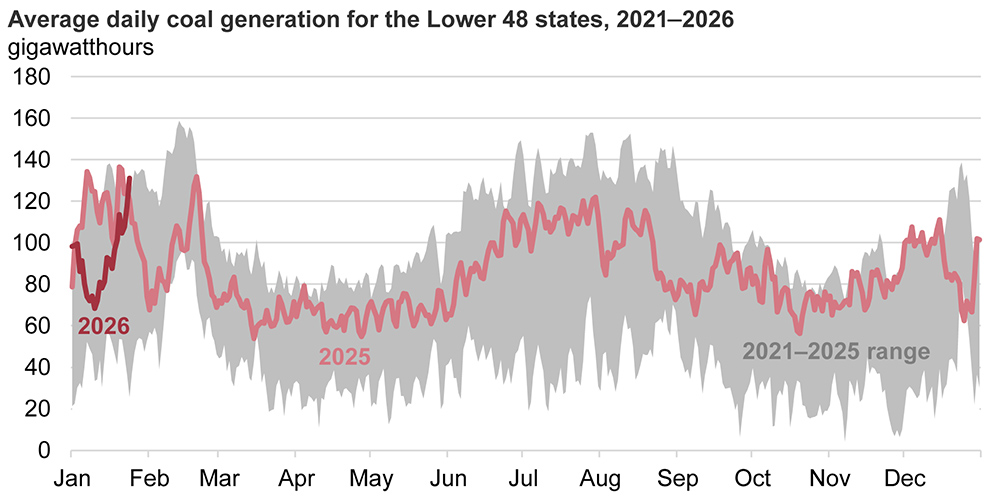

While prices spiked across multiple markets, the grid remained intact. There were several major reasons for that, with the underlying factors varying by region, but thermal plant reliability was a key theme. Gas generation was a critical player, but coal and oil also filled the gaps to meet surging demand. A review of several grids illustrates the point.

-

- ISO-NE: New England saw dual-fuel plants switch over from gas to oil, burning through about half of the region’s stored oil reserves in late January and early February, with oil-fired generation surpassing gas for a couple of days. The grid operator requested a Department of Energy waiver to avoid emissions penalties.

- PJM: The Mid-Atlantic grid operator commented that during the “strongest sustained cold period that the PJM system has experienced since the 1990s” it saw an average 18 to 19 GW of outages (compared with an expected 15.9 GW), with plant equipment failure as the greatest cause. Tight gas supplies also were a concern. In response, PJM called upon 5.2 GW of oil-fired capacity “that would otherwise have been restricted,” aided by a DOE order waiving emissions restrictions.

- MISO: MISO ran coal generation more heavily than normal, including three of the five coal plants whose retirement was delayed by the Trump administration, delivering a total of 965 MW during much of the period from Jan. 21 to Feb. 1.

- ERCOT: ERCOT also made it through, with its improved weatherization and inspection programs of power plants and transmission facilities reducing generation outages. Increased reserves, more flexible operations (including increased dual-fuel capabilities) and a growing deployment of batteries also helped.

We learned, once again, that our nation’s power grids rely on a significant fossil mix when the weather turns nasty. Coal-fired generation soared across the lower 48 states during the week ending Jan. 25, up 31% from the prior week and representing 21% of power generation, while gas stood at 38% and nuclear at 18%.

We also learned that events on the grid are increasingly ripe for being politicized. Less than two weeks after the storm had passed, DOE issued a fact sheet declaring that “Beautiful, clean coal was the MVP of the huge cold snap we’re in right now,” and decrying the actions of the previous administration’s “energy subtraction policies which threatened America’s grid reliability and affordability.”

It seems that such politics are sadly unavoidable these days. But let’s try and remove politics from the conversation and focus on the facts. It’s not controversial to state that during the coldest days that occur every so often, fossil thermal generation — whether oil, coal or gas — is extremely valuable in keeping the lights on. Renewables and storage can pitch in, but they are a long way away from being able to handle that task.

As an example, when this article was drafted (Feb. 13), renewables made up 10% of the generation mix in ISO-NE at 3:30 p.m. In addition, on this clear and sunny day, rooftop solar cut peak demand by about 5,000 MW, with the duck curve exerting its influence on net demand. So, a combination of utility-scale and on-site renewables can generate energy and cut the use of fossil fuels.

However, that solar doesn’t address the evening peak, and it doesn’t help after heavy snow. The day after Fern departed New England, nearly all the panels in the region were blanketed with snow and the duck was hibernating, with no visible impact to be seen. As a dependable resource that can provide both capacity and needed energy, neither variable wind nor solar check the box.

Batteries can help meet peaks and address this issue of renewable energy droughts, if those storage assets can be fed by renewables, and renewable energy shortfalls are of relatively limited duration. That equation may change if we eventually get the long-duration, 100-hour batteries promised by start-up companies such as Noon and Form Energy, and those storage resources are deployed in enormous quantities at affordable prices. But we’re not there yet.

Addressing the Demand-side Thermal Issue

At the same time, much of the peak demand that occurs during extreme cold or hot spells could be greatly mitigated if we started to more accurately frame those peaks as a thermal problem, stemming from the need to heat or cool our built spaces. The better we insulate those spaces, the less volatility we would see in resulting energy demand.

EPA reports that homes can save an average of 15% on heating and cooling costs by employing a variety of insulation technologies. This need not be a herculean task, and insulation is effective. For example, upgrading U.S. homes to a 2009 building code could keep residences above 40 degrees Fahrenheit for nearly two days in sub-zero temperatures.

Maintaining a reliable and cost-effective grid is not, and never has been, a strictly supply-side issue. Rather, the power grid’s various supply and transmission technologies, combined with demand-side technologies, comprise a massive system of systems that can best be made economical, reliable and resilient if it is viewed and addressed as such. But such an approach requires sophisticated thinking that defies the simplistic and easy answers that many politicians and some analysts proffer.

Climate is an Even More Complex System of Systems

Perhaps counterintuitively, the polar vortex breaks down when it experiences spikes in the stratospheric temperatures, known as sudden stratospheric warmings. When those breakdowns occur, some areas of warmer air pour into the Arctic while lobes of polar air flee southwards. Nobody fully understands the dynamics behind this, but models suggest that climate change may be a driving force. If so, then we can add that to the lengthy list of other climate-related issues that justify cutting carbon emissions from our energy systems.

To pretend that we can oversimplify either the power grid or the impacts of human activity on the earth’s climate is a mistake. Each of these complex systems — and their interactions with each other — deserves far more scrutiny and understanding than most of us are willing to devote. We need more data and information, not less, and to entertain more nuanced conversations as well.

Around the Corner columnist Peter Kelly-Detwiler of NorthBridge Energy Partners is an industry expert in the complex interaction between power markets and evolving technologies on both sides of the meter.