When solar and the grid are mentioned in the same breath, acres of shining panels come to mind. But it’s time for rooftop solar to become a part of that vision, not the peripheral realm of hippies and preppers. Two milestones were reached that reinforce why the United States needs to take rooftop solar seriously and how it can be an essential part of our energy mix.

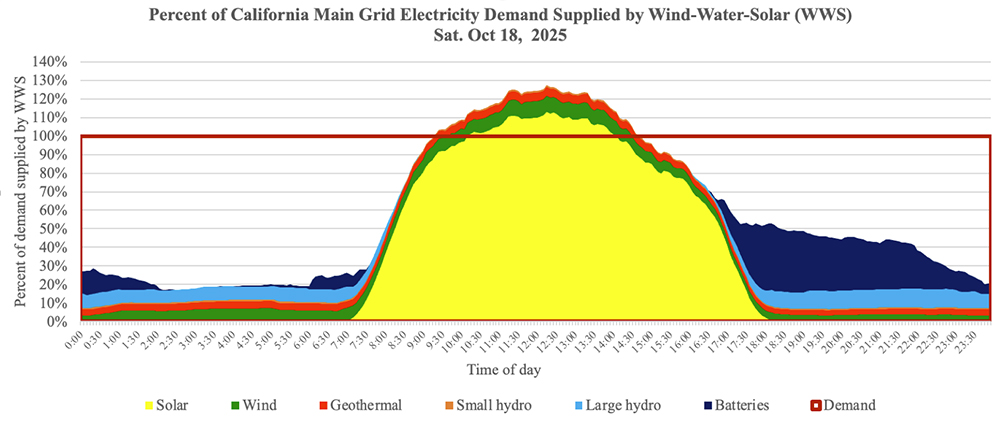

On Oct. 18, California clocked its 200th day of 2025 where wind, solar and hydro supplied 100% of the main grid’s needs for part of the day, a milestone noted in a LinkedIn post by Stanford University professor of civil and environmental engineering Mark Jacobson. That means that more than two-thirds of the days in 2025 have had times where renewable energy production was so high that its output was curtailed or, one hopes, stored in batteries for later use.

Yet as impressive as that was, it excluded the significant contribution of rooftop solar.

The Role of the Rooftop

As California hit its 200th day with 100% of demand met by renewables for a slice of the day, a different milestone was being reached Down Under.

South Australia achieved greater than 100% of its “operational demand exclusively from rooftop photovoltaics” for the 13th time since September 2023, John Noonan, a consultant who watches Australia’s electricity markets closely, responded to the post celebrating California’s milestone. His comment led me down a rabbit hole, exploring the energy system of my homeland, how it’s become the world’s leader in rooftop solar and what that means for the grid.

When you talk to many grid operators in the United States, rooftop solar is perceived like homemade goodies at a bake sale: cute, but hardly a threat to Big Cake. It’s only in states like Hawaii, Massachusetts and California where the sum of the rooftop systems is considered significant that it’s seen as an integral part of the energy system.

In California, utility-scale solar supplied about 19% of the state’s total electricity net generation in 2024, and when small-scale systems (less than 1 MW) are included, that increases to 32%. The majority of small-scale systems are residential rooftop systems.

To See the Future, Look South

To see what the grid could look like when rooftop solar is not just common but plentiful, we need to look south, as far south as South Australia, the country’s fifth-most populous state.

Of course, Australia and the U.S. are wildly different: Australia is about the same size as the contiguous lower 48 states, with a population smaller than Texas’, and South Australia is about 1.5 times the size of Texas with a population like Idaho’s. But the two countries have similar housing stock, with around two-thirds of households in single-family homes and two-thirds of those homes owner-occupied.

Where they differ massively is in solar penetration: South Australia leads the world in residential solar installation density, with 54% of homes having rooftop solar.

In Australia’s other state with more than 50% penetration, Queensland, residential and business rooftop solar broke records recently, contributing more than 5 GW (>52%) of state demand on a day that set new springtime temperature records.

Can There be Too Much Rooftop Solar?

In late 2022, South Australia had a chance to answer that question. A storm toppled a 275-kV transmission tower, severing the state from the national electricity market. Suddenly, rooftop solar provided more than enough power to the then-isolated state grid, and the grid operator remotely turned off 400 MW of rooftop solar to ensure grid stability. Why? According to the Institute for Energy Research, “if rooftop solar can meet all or most of local demand, there is little or no firm capacity available for the system operator to use if another major incident affects the grid.”

This is where deployment of batteries, both behind-the-meter and utility-scale, comes into play. Rooftop solar is a grid asset when grid operators can use batteries to play the crucial role of firm capacity. Referring to blackouts in Spain and Portugal earlier in 2025, RMI said: “If U.S. grid planners wish to learn from the Iberian Peninsula’s story, there is one resource that has proven it can compete to provide grid stability and affordability at the same time: batteries.

“Batteries can support all three main components of grid reliability: resource adequacy — the long-term ability to meet demand on peak; stability (also known as operational reliability) — critical short-term services like frequency and voltage regulation that stabilize the grid; and resilience — the ability of the grid to quickly recover from or support critical systems during an outage.”

On Track to 100% Renewables

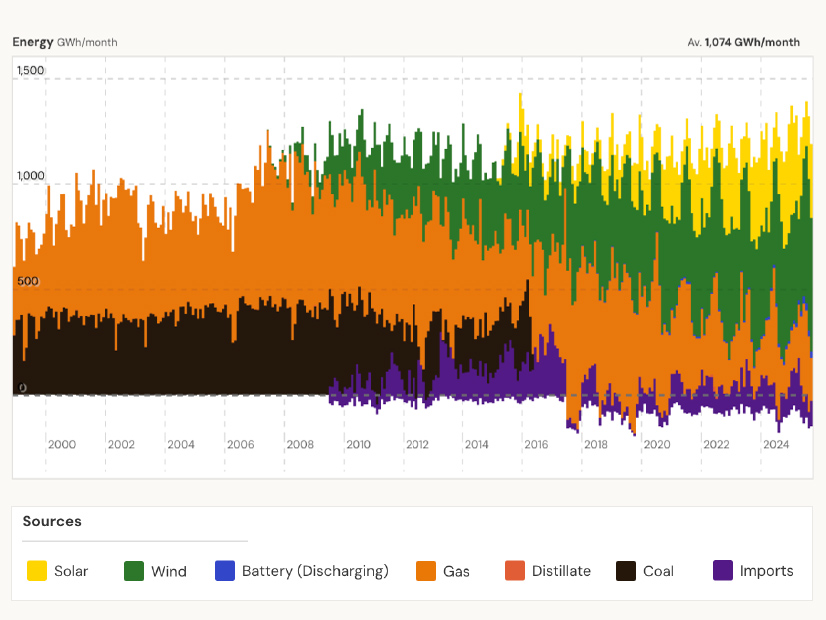

In Australia, rooftop solar is not simply a nice bonus that supplements utility-scale electric generation during peak demand; it is an essential slice of the power supply as the country moves to 100% renewables. And, not surprisingly, utility-scale electric generation no longer is dependent on fossil fuels, though they are far from fully phased out.

Utility-scale solar and wind have been significant in Australia for some time, and the country is ramping up deployment of utility-scale energy storage to enable it. In August, renewables provided more than 47% of all grid power for a time, setting a record.

There still are some highly polluting fossil fuel power plants on the grid. For example, brown coal — a wetter, and therefore less efficient, type of coal also called lignite — still powers half of my home state of Victoria’s grid, with the country’s largest brown coal mine supplying two power plants that feed 3.4 GW of base load into the grid.

But despite the current dependence on fossil fuels, most states are setting bold goals to phase them out. In July 2024, South Australia signed a Renewable Energy Transformation Agreement with Australia’s federal government, setting a goal to meet 100% of its electricity needs with wind and solar by 2027. Since then, all but two of the country’s states and territories have signed on.

Rooftop’s Role in National Goals

A transformation of the scale of Australia’s is hard to imagine without the strength of its rooftop solar market.

In any country with a strong rooftop solar market, its growth didn’t happen in a vacuum: policies such as feed-in tariffs, net metering and tax credits supported the industry. That’s why not-particularly-sunny Germany took the early lead in the global market. In Australia, where sunshine is plentiful, generous feed-in-tariffs encouraged many homeowners to adopt rooftop solar, though a widespread desire to stick it to the utilities tipped the scale.

Today, 38.7% of the 10.9 million Australian homes have solar, and 5% of those also have batteries. Compare that to the U.S., where just 7% of homes have solar, a number not likely to double until 2030, and even that’s in question given recent political headwinds.

Globally, rooftop solar will continue to grow. The DNV Energy Transition Outlook 2025 said plunging costs of solar and battery hardware mean that behind-the-meter solutions “will represent 30% of all solar and 13% of all power generated by 2060.”

Even in markets with high solar penetration, growth will continue as batteries are added to solar systems, both new systems and those undergoing retrofit. Those batteries provide the critical energy storage that enables solar generated at the height of the day to be consumed during early evening peak consumption.

Toward Baseload Rooftop PV

Energy storage is essential if rooftop solar’s large share of generation is to be considered as baseload power, Noonan said: “The frequency of these 100% operational demand reports from South Australia is going to become routine as South Australia begins to define the concept of ‘baseload rooftop PV’ when paired with large behind-the-meter industrial-scale, commercial-scale, residential-scale and battery electric vehicle-scale grid-forming (GFM) synthetic inertia (SI) battery energy storage systems.”

Energy storage is important to the economics of the rooftop solar industry. The DNV outlook said installing stand-alone solar has become less profitable in regions with higher rooftop solar penetration and time-of-use tariffs, such as Australia, Germany and Spain. “Focus is shifting instead to solar+storage systems, where prosumers store excess energy and use it during peak-price periods to maximize savings. This is also supported by growing adoption of dynamic feed-in rates, declining lithium-ion battery costs, and evolving grid tariffs, taxes and levies.”

The same trend is being seen in the U.S. In California, for example, batteries are paired with more than half of new residential solar systems.

Solar’s Momentum Needs Steady Policy, Low Prices

In the U.S., state rooftop solar markets start and stop like an old car needing a tune-up. Residential solar in the U.S. has a reputational problem — arguably because of the industry’s sales and financing methods — with 40% of homeowners believing it is hard to find a trustworthy installer. And with multiyear payback periods and the lingering stain from some sales practices, selling solar is a struggle in many markets.

In 2025, the U.S. rooftop solar market’s struggles have grown: state-level battles over feed-in-tariffs and net energy metering policies are a constant challenge, and now federal tax credits face early termination at the end of the year.

Rising concern about the reliability of the grid in the U.S. is countering these headwinds. Grid reliability — a problem perceived by more than half of homeowners — is becoming one of residential solar’s strongest selling points. Before the recent federal policy changes disrupted the economics, 76% of homeowners saw solar as a good investment, according to an Aurora Solar survey: surprisingly high given how few of them have actually invested in a home solar system.

Yet the biggest issue slowing rooftop solar in the U.S. is price: the industry sees no end to the burdensome soft costs — especially permitting hurdles that vary by town — that drive prices up to three or more times those of comparable systems in Australia. The resulting high installed-system prices make payback periods two to three times longer than in Australia, and the loss of the federal tax credits will tack on another year.

While we struggle to restart the market after each policy bump in the U.S., in Australia, its momentum is unstoppable. Why? Because it’s so damn cheap.

Australia’s rooftop solar is dramatically cheaper than in the U.S., so much so that Saul Griffith, MacArthur Genius and author of Electrify, said Australian rooftop solar is “the cheapest retail energy ever provided to a consumer in human history. It is extraordinary.”

Beyond Federal Policy: What We Can Do in the Meantime

For as long as I’ve followed the U.S. residential solar market, there has been talk of cutting the soft costs so American rooftop solar is competitively priced by global standards. Industry and government efforts have failed so far.

I’ve heard solar installers rail against my neighboring city, where permits cost thousands of dollars, take weeks and require five copies of paperwork, much of which is gratuitous. Two cities over, the same system gets a permit in 15 minutes at a reasonable cost, with simple electrical line drawings.

The Department of Energy’s admirable SolarAPP+ program was supposed to do what the industry failed to do: streamline permitting across the thousands of local permitting jurisdictions so that adding solar to a home has no more red tape than, say, electrifying appliances or adding home EV charging.

If America’s distributed energy system is to flourish, the states need to get together and do what the federal government no longer cares about. It’s a strategy that blue-state governors are using to address health care costs. They could easily do the same for rooftop solar by rolling out the existing SolarAPP+ program across every town and city in their states. Similarly, if PUCs pushed for rapid interconnection of home solar systems, going solar would be less frustrating for installers and homeowners.

If permitting and interconnection become cheap, fast and easy, the cost of residential solar should fall enough to offset some of the loss of the federal tax credits, and perhaps even the tariffs on imported system components. And if all of that leads to simpler sales and fewer buyers bailing mid-process, costs will become even more competitive.

Rooftop solar — and the grid that benefits from it — deserves the same coordinated approach many states are giving health care. Doing so will protect thousands of jobs, offer American homeowners a way to get reliable and affordable energy, and improve grid reliability.

Power Play Columnist Dej Knuckey is a climate and energy writer with decades of industry experience.