Many of the hyperscale data centers being built around the country are using less efficient, dirtier natural gas generation as part of their race to get more computing power online, says a new report from clean energy advocate Cleanview.

Some 46 facilities with 56 GW of power demand are planning to build their own behind-the-meter generation, which represents 30% of all planned data center capacity in the country, according to Cleanview research.

“There’s been this huge surge in data center demand and data centers wanting to connect to the grid, and that has resulted in the timeline to connect to the grid exploding,” Cleanview CEO Michael Thomas said. “It can now take as long as seven years in some markets like Virginia to connect. And then it’s also put a huge amount of pressure on turbine supplies.”

Just three manufacturers make the most efficient combined-cycle natural gas turbines, and the wait time for them has grown in recent years. Some had thought that combination would throttle data center development, but Thomas said they have found creative ways to get generation capacity with many facilities already under construction.

“What these data center developers are doing is installing gas turbines on semitrucks and driving them in so they can install them in weeks, not years,” Thomas said. “They are repurposing aero-derivative turbines that were originally designed for airplanes, warships and in some cases even cruise ships. And then they’re using these backup generators and engines that companies like Caterpillar have traditionally sold as backup power to be used a small number of hours in a year, and they’re using those essentially 24/7.”

Those types of generators are less efficient than combined-cycle plants, and they produce more pollution, whether local pollution like nitrogen dioxide that can make their neighbors sick or climate pollution.

The Stargate Project in New Mexico, being built by OpenAI and Oracle, is about 2 GW and will emit 15 million tons of CO2 per year.

“Over the last 20 years, New Mexico, as a whole state, has decarbonized its economy by 15 million tons, and they’re one of the leaders,” Thomas said. “And so that single data center would wipe out all of the state’s decarbonization.” (According to its website, Cleanview’s mission is “to accelerate the clean energy transition.”)

Massive data center developments using whatever generation they can get their hand is a growing trend. It started in Memphis, Tenn.

“A little more than a year ago, this was just a niche phenomenon,” Thomas said. “xAI, famously owned by Elon Musk, was one of the first to do it in Memphis. A few others have kind of experimented with it, but it was really niche. Now it’s become one of the most popular strategies. So, 90% of the projects that we identified, representing about 50 gigawatts, were announced in 2025 alone. We’ve seen this huge explosion in that trend.”

The report was based on data from the facilities permits, SEC filings, utility regulatory filings and press releases, though Thomas noted the press releases often focus on cleaner generation and leave out the use of inefficient generators.

Musk’s Colossus AI data center was built in an area of Memphis that already was overburdened with pollution, and that led to significant pushback. The NAACP sued xAI over air permits and has launched an effort to fight similar projects as they arise. (See NAACP Event Examines Data Center Impact on Environmental Justice.)

Most of the data centers identified in the report are being built in more rural areas, in part to avoid the political pushback encountered by xAI, but also to gain better access to natural gas and an easier permitting process. Only one of the data centers from the report using behind-the-meter generation is in a city, Thomas said.

That data center, in San Jose, Calif., “will be built with Bloom fuel cells, which results in far less air pollutants,” he added.

Wind, solar and storage do not face the same kind of timelines as combined-cycle generation, but they do make developments more difficult because of greater land use, Thomas said.

“These are already thousands of acres for the data center alone, and then if you add on top of that, many more thousands of acres for solar and wind data center, developers might be concerned that it’s just harder to lock up that land, or it’s harder to permit that, or maybe it sparks more backlash,” Thomas said.

Across the 56 GW highlighted in the report, there are significant differences in how the data centers plan to relate to the grid in the near term and over time, said former FERC Commissioner Allison Clements. She’s now a consultant at 804 Advisory and a partner at Appleby Strategy Group, which advises data center developers.

“For some, onsite generation is intended as a bridge until more reliable grid power becomes available,” Clements said. “In any case, the report affirms that the high-octane speed-to-power craze is real, and that substantial capital is willing to pay big bucks and take on stranded-cost risk.”

The enduring strength of that demand is uncertain, but utilities would be wise to unlock more capacity on their systems quickly.

“Regulators can support these efforts by moving swiftly to align incentives around fast, lower-cost tools like advanced transmission technologies, rapid battery deployment and portfolios of distributed energy resources,” Clements said.

The Cleanview report’s findings were highlighted by another close watcher of growing power demand, with Grid Strategies Vice President John Wilson highlighting the report at the National Association of State Energy Officials conference Feb. 4.

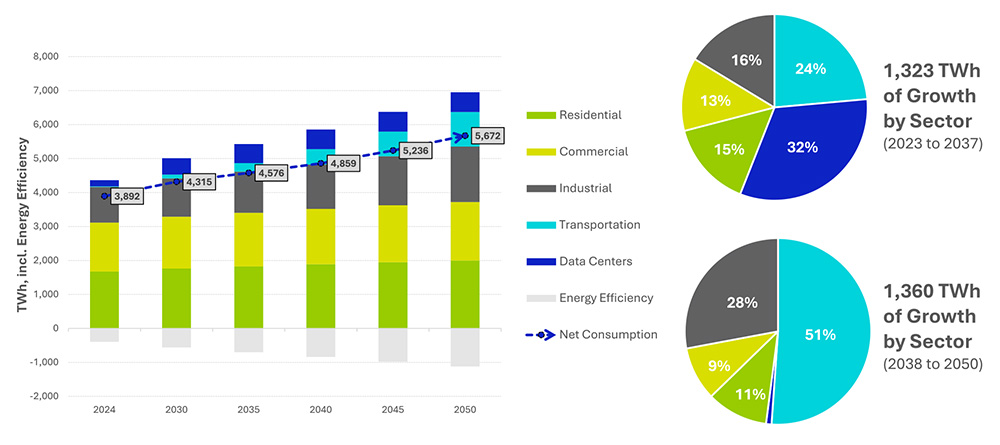

Wilson is behind the firm’s load forecasting reports, which show up to 90 GW of data centers planned to come online in the next five years, though that could be limited to 65 GW because of chip shortages. (See Grid Strategies: Pace of Load Growth Continues to Speed up.)

The Cleanview report shows that many of those data centers are not using the cleanest gas generation, he said.

“Most of this natural gas generation that’s going in is not highly efficient, modern gas generation, it is less efficient — whatever they can get, literally generators-on-the-back-of-a-truck kind of generation,” Wilson said. “This is what is in their permits.”

In five years, the industry could add more data center demand to the national grid than ERCOT’s record peak, Wilson said. “A year ago, we were really not looking at this, and now 40% plus of the large load growth is from these gigawatt-scale data centers, 500 MW-plus — mostly AI,” Wilson said. “The idea of a gigawatt-scale load was just not something that most utilities considered a possibility five years ago, much less 2, 3, 4 GW at a single location.”

Traditionally such major power demands would be served by combined-cycle turbines, but the demand for those has led to lengthy lead times, which clash with the massive financial incentives for data center developers, Thomas said.

“A data center like this, built by developer, can, right now, sell that capacity for between $10 billion and $12 billion per gigawatt,” he added. “So, the opportunity of coming online in just six months or a couple years early is huge, and so they’re willing to pursue these strange strategies.”

AI applications are not making that much money yet, but the firms involved in the industry like Meta or Microsoft are the largest in human history, with massive balance sheets. They worry about being left behind by a potentially major leap forward in technology. They had been sitting on large stores of cash for years, which now are being spent on data centers and related infrastructure, Thomas said.

The trend the Cleanview report put firm numbers around had been picked up by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), which recently posted about the possibility of using old jet engines from a facility on Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona colloquially known as “the Boneyard.” Data centers in Texas recently deployed modified jet engines as generators that can each produce 48 MW, EIA said.

The engines from the fallow planes at the desert facility could produce a total of 40 GW, which beats the current installed generation in the state of Arizona by 10%, EIA said. But the engines are old, averaging more than a decade, and the military has its own uses for them — so the actual capacity is far less.

The burst of data centers being built with creatively sourced generators means additional demand for natural gas, which increasingly is being exported via LNG and faces higher demand from the combined-cycle plants that also are being built, said Public Citizen Energy Program Director Tyson Slocum.

“The era of cheap gas is over,” Slocum said. “All of this new gas, build for power generation, is going to be very expensive.”

In 2025, the eight export LNG export terminals used more of the fuel than the 74 million Americans served by natural gas utilities, he added.

So far, data centers have affected power prices most visibly in PJM, where its capacity prices have surged as its reserve margins have narrowed. While supply might catch up to demand and lead to lower capacity prices eventually, Slocum asked how many more billions of dollars that would take.

“I’ve heard this argument in competitive markets since the beginning — ‘Well, folks just need to pay a little more, and then the market will balance itself out,’” Slocum said. “And then right when it’s supposed to balance out, they’ll say, ‘Gosh, we need more transmission.’ Or whatever the argument is going to be, there’s always some caveat.”

If data centers are not part of an AI bubble and LNG exports continue unabated, gas prices will be high, and that translates directly into higher energy prices across the country, he added. Then, laying on the legitimate issues around pollution on top of the costs leads to questions about the value of the “AI race.”

“My big issue here is that we’ve got big tech and their supporters in the administration saying the artificial intelligence race is of national security importance,” Slocum said. “Well, says who? Says a bunch of tech companies that stand to make massive profits by commodifying and locking us into their products? We have not had a national conversation about the scope of AI’s application in our society or in our economy.”