BOSTON — While there is near-universal recognition that New England will need to add a significant amount of new generation over the next two decades, conflicting political and market forces have created major uncertainty about what the next wave of generation projects will look like.

This uncertainty extends to how the region will spur the development needed to meet demand growth, several speakers said at a Northeast Energy and Commerce Association conference on power markets in Boston on Jan. 29.

The scale of the need could be substantial: ISO-NE forecasts peak load roughly doubling by 2050, and decarbonization would require additional clean energy to replace much of the existing fossil fuel fleet.

Incentivizing new generation solely through the wholesale markets may be a difficult proposition. Although energy affordability has dominated policy discussions over the past year, wholesale market prices had remained relatively low until the past two months, which have brought a major increase in energy costs due to sustained cold weather. (See Cold Weather Drives Record December Energy Costs in New England.)

Dan Dolan, president of the New England Power Generators Association, said there has been a “dramatic disconnect” between consumer costs and wholesale market prices. For generators relying on capacity and energy revenues, “if anything, there’s a revenue crisis.”

With consumer prices already high, the increased energy and capacity prices needed to spur new development could lead to political backlash and caps on market prices.

This dynamic has occurred in PJM, where “we’re just now seeing these markets shifting from being long on capacity to being more at equilibrium,” said Ben Griffiths of NRG Energy. “It’s not clear that the prices that [power developers] would require to bring in new entry are actually politically feasible.”

If market prices alone are not enough to bring new generation online, the New England states could assume an even larger role in the procurement of new generation and capacity. But continued reliance on state power procurements would bring its own set of difficulties.

Connecticut’s 10-year power purchase agreement with the Millstone nuclear plant has demonstrated some of these challenges. The difficulty of reconciling PPA costs through rates has led to major swings in the monthly costs to consumers, and Connecticut officials have been pushing for other states to shoulder some of the plant’s costs after the current contract expires in 2029.

Griffiths noted that former ISO-NE CEO Gordon van Welie had pushed the states to take on a larger role in capacity procurement through bilateral contracting.

He added that the region could consider capacity market changes aimed at increasing revenue certainty, such as altering the demand curve to stabilize prices or reintroducing some version of a price lock for new capacity.

But he expressed skepticism about the long-term sustainability of the proposal by the PJM state governors and the White House’s National Energy Dominance Council for a one-time “backstop” auction to procure 15-year contracts with new capacity resources. (See Government-proposed ‘Backstop’ Auction to Test PJM Stakeholder Process.)

“It doesn’t feel long-term sustainable to have bifurcated markets that are providing the same benefits in real time,” Griffiths said, adding that he is “increasingly skeptical of the approach of trying to move all the money out of the capacity market.”

Bob Ethier, current PJM board member and former vice president of system planning at ISO-NE, stressed the need for longer-term solutions to high costs.

“The tension that I see is that there are times where we can do things in the short term that will lower bills but will hurt the market’s functioning in the long run,” he said, emphasizing the importance of maintaining long-term entry and exit signals in the market.

Multiyear price locks for capacity could help reduce year-to-year price volatility, he said, adding that states may be better situated to pursue this strategy than RTOs. He emphasized the need to have these conversations prior to price spikes.

Once a crisis hits, like in PJM, “all we can do is ride [it] out, tweak things around the edges and hopefully learn from it for the next one.”

Policy Pickles

Conflicting objectives between federal and state policies have also added significant challenges and uncertainty to resource development, several speakers said.

“We’re in a pickle in the region for what we can build and what is a sound investment,” said Matt Nelson, principal at Apex Analytics and former chair of the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities. “We’ve lost some tailwinds and are picking up a lot of headwinds when it comes to clean energy policy.”

Despite the load growth projections and increased demand over the past two years, there is a relatively small amount of generation in the ISO-NE interconnection queue. The first iteration of the Order 2023 cluster study process, initiated by ISO-NE in October, includes 5,632 MW of storage, 355 MW of solar and the 1,200-MW SouthCoast Wind project, which faces considerable challenges from the Trump administration. (See Storage Projects Dominate ISO-NE Transitional Cluster Study.)

Nelson said each new resource category has its own drawbacks: New gas generation seems unlikely with the region’s winter gas constraints and grid’s current “overreliance” on gas; new nuclear looks to be at least 10 years out; the federal government appears to have taken offshore wind off the table; and large-scale solar development faces questions about the loss of federal incentives and a potential capacity revenue hit from ISO-NE’s proposed accreditation changes.

To address load growth amid so much uncertainty about sources of new development, the region must build consensus around a cohesive plan, Nelson said. He added that distributed solar and storage may play an increasingly large role over the next few years.

“State programs are about the only thing left where clean energy resources can get an incentive,” he said.

Aaron Lang, a lawyer focused on clean energy development at firm Foley Hoag, said renewable developers are dealing with “a mountain of uncertainty” related to tariff policy and other potential state and federal policy changes over the past year.

“The pressure is really on the states to do a lot of stuff,” he added, while expressing some optimism about Massachusetts’ efforts to establish a new consolidated permitting and siting process for clean energy resources.

The new process stems from climate and energy legislation passed by the state in 2024. Under the new rules, developers must apply for consolidated state and municipal permits, with the permitting review process limited to 15 months for large projects and 12 months for smaller projects.

The law requires the state to promulgate final regulations by March 1. The state plans to start processing projects through the new process in July.

While there may be some short-term “bumps in the road,” the new process should provide long-term benefits for resource development, he said. “The idea of a consolidated permit is an excellent idea.”

Consumer Cost Drivers

Over the past couple years, New England has seen electricity prices rise faster than inflation, though the inflation-adjusted rate of increase has been relatively modest for most of the region, said Todd Schatzki, principal at the Analysis Group. When accounting for use and rates, customer costs have fallen since 2010 but have risen since 2020, he said.

He emphasized that the cost increases are not felt equally by all customers, with larger impacts on residential customers who have not seen wage growth in line with inflation.

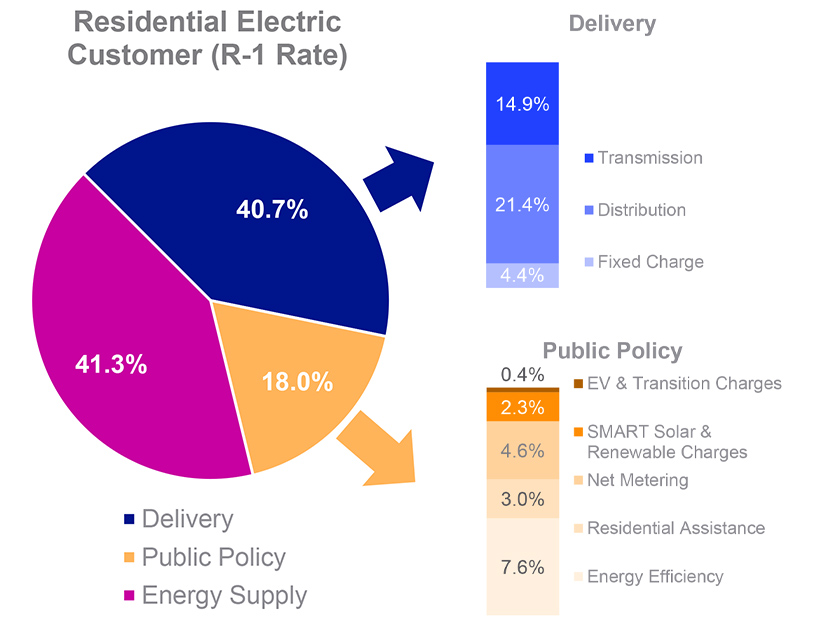

Sandy Grace, vice president of U.S. policy and regulatory strategy at National Grid, presented a cost breakdown of a typical Massachusetts residential electric bill for November. The main cost categories were energy supply (41.3%), distribution (21.4%), transmission (14.9%), energy efficiency (7.6%), net metering (4.6%) and utility fixed charges (4.4%).

“It really does require a partnership across sectors to address these costs,” she said.

Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission Chair Ron Gerwatowski focused much of his remarks on the rise of transmission rates in the region.

Asset condition spending, or investment to address degradation of existing transmission infrastructure, has risen significantly in recent years and makes up the bulk of new regionalized transmission spending in ISO-NE. The rising costs, coupled with the limited regulatory scrutiny the spending receives, has prompted efforts to establish internal asset condition review capabilities at ISO-NE.

While this role would not be a regulatory entity, it would be intended to increase transparency into projects and provide information that could be used by third parties to challenge project costs with FERC.

“Quite frankly, it may not be enough,” Gerwatowski said. “We need the transmission owners to temper their appetite for investment in asset condition projects.”

If transmission owners do not scale back their spending, the states may be forced to try to step in and do it for them, he said, noting that states “still control both the method and the timing” of how transmission rates are recovered.

Instead of allowing the quick recovery of transmission spending as pass-through costs, the states could require the recovery of transmission costs through the full base rate case process, he said.

Introducing regulatory lag “could give the financial folks an incentive to push back” on asset condition spending, he said.

If state regulators have little or no confidence in the asset condition planning and development process, he added, “What other options do we have?”