The latest in a series of Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) reports on the costs of the AI boom asserts that powering U.S. data centers with clean energy would avert trillions of dollars in health and environmental costs.

The report, issued Jan. 21, warns about the public potentially paying twice for the massive data center buildout many observers expect — first to cover the cost of new grid infrastructure, then a second time for the negative impacts of that infrastructure if it relies heavily on fossil fuels.

“Overall, our modeling demonstrates that clean and renewable energy can meet the challenge of load growth from data centers, but policymakers must be proactive to protect our health, environment and financial interests,” Director of Energy Research and Analysis Steve Clemmer said in a news release announcing the study.

“Data Center Power Play: How Clean Energy Can Meet Rising Electricity Demand While Delivering Climate and Health Benefits” does not present green power generation as a direct cost savings — decarbonizing the power sector would instead increase U.S. wholesale electricity costs $412 billion or 7%, it says.

Restoring federal clean energy tax credits to the levels in the Inflation Reduction Act would shift the cost off ratepayers and lower electricity costs by $248 billion or 4%, the authors write.

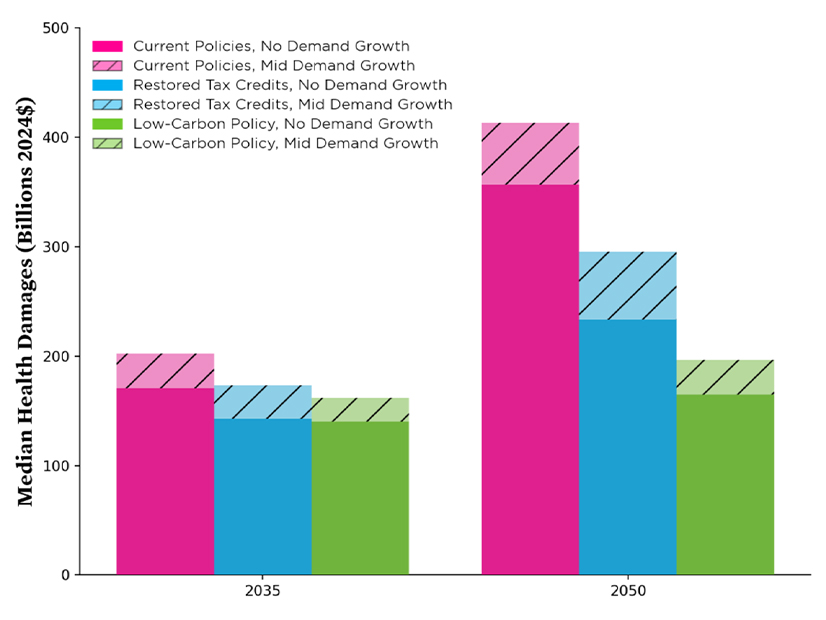

Both figures would be dwarfed by the $8 trillion to $13 trillion in cumulative global climate benefits and the $120 billion to $220 billion in cumulative health benefits expected to result from decarbonization by 2050, the authors write.

That is a tradeoff the present team of federal policymakers appear unlikely to make, but the report also calls for state policymakers to take action to avoid financial, health and environmental impacts harms associated with unchecked growth of data centers.

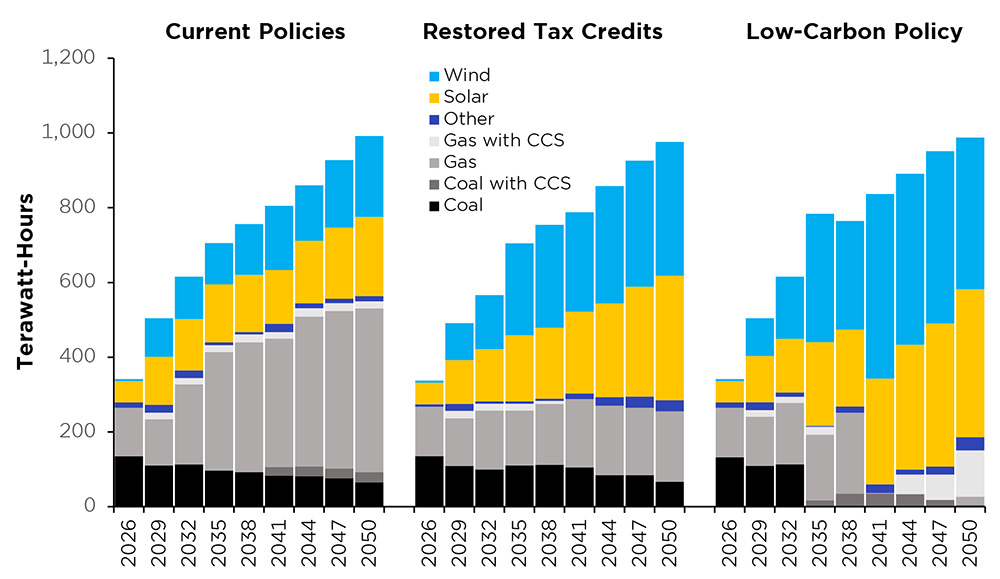

The analysis looks at three scenarios: the current policy landscape created by the Trump administration and its allies in Congress; restoration of electricity tax credit provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act; and a national effort to reduce the power sector’s carbon-dioxide emissions 95% by 2050. It uses a midlevel assumption for data center demand growth but adds a no-demand growth comparison to isolate the impacts of data centers.

The study estimates that:

-

- Data center demand could increase from 31 GW in 2023 to 78 GW in 2030 and 140 GW in 2050.

- More than 90 GW of new gas-fired capacity would be added by 2035 and 335 GW by 2050 under Trump administration policies.

- Coal-fired generation as a percentage of the whole would decrease by 2035 and 2050 under all three scenarios.

Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin

The report is accompanied by a technical appendix, as well as breakouts drilling down on projected impacts in three Upper Midwest states.

“Looking collectively at our findings for Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin, it’s clear that strong, foundational state clean energy policies are helpful for confronting the large — yet highly uncertain — data center-driven growth in electricity demand,” said James Gignac, UCS Midwest policy director. “But without careful, specific attention by state policymakers and regulators to data centers, the rapid rise in the need for power leads to increased costs and pollution.”

UCS noted Illinois has strong power sector decarbonization policies but said more is needed, because without further policy protections, data center-driven load growth could put Illinois at risk of $24 billion to $37 billion in additional electricity system costs.

It said data centers could account for up to 72% of electricity demand growth in the state by 2030. But current policies will increase the use of in-state fossil fuel plants and increase reliance on out-of-state generation, UCS said.

Michigan too has enacted significant clean energy legislation in the 2020s, UCS said, but lawmakers left a loophole: The restrictions apply only to electricity sold within the state, not to energy generated in-state but exported to other states.

UCS recommended that Michigan close that loophole.

It also said Michigan’s electricity demand could nearly double by 2050, with data centers accounting for up to 38% of the increase, but said those estimates were highly speculative. It called for greater transparency from data center developers and flexible utility planning.

UCS said Wisconsin does not have comprehensive clean energy policies in place but is experiencing a data center development boom. Current policies would prompt large increases in natural gas generation with accompanying increases in carbon emissions.

UCS recommended that Wisconsin commit to clean energy policies now; adopt ratepayer protections that require data centers to bring their own clean energy generation; be transparent about decision making; and impose integrated resource planning requirements on utilities.

It did note movement in Wisconsin’s statehouse in 2025 on measures intended to reduce economywide carbon emissions and protect consumers from the costs and carbon emissions of new data centers.

As of 2023, coal- and natural gas-fired power plants provided 75% of Wisconsin’s in-state generation, UCS said.

Methodology

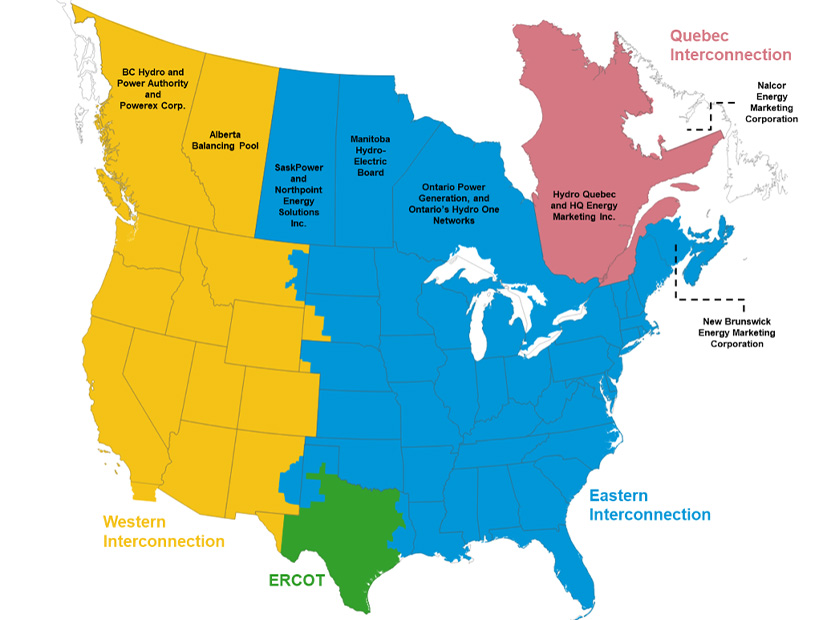

The UCS analysis uses the Regional Energy Deployment System, a least-cost electricity planning and dispatch model developed by what was then known as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and it relies on electricity demand projections developed by Evolved Energy Research for its Annual Decarbonization Perspective 2024 report.

The concept of flexible data center demand — recently gaining much attention as a means of reducing peak load and reducing the need for new infrastructure — was not included in the analysis, nor were impacts of recent market and policy changes, such as new tariffs, rising gas turbine costs, natural gas price volatility and federal road blocks to renewable power development.

New nuclear capacity — another priority of the Trump administration — was not modeled because of its high cost. Also not modeled was Big Tech’s interest in paying above-market prices to restart or uprate existing nuclear plants, or in building new reactors to power data centers.

Finally, the authors note that the number of data centers to be built and the amount of electricity they will consume are both highly uncertain. Also unknown are technology advances that may change the energy profile of future data centers.