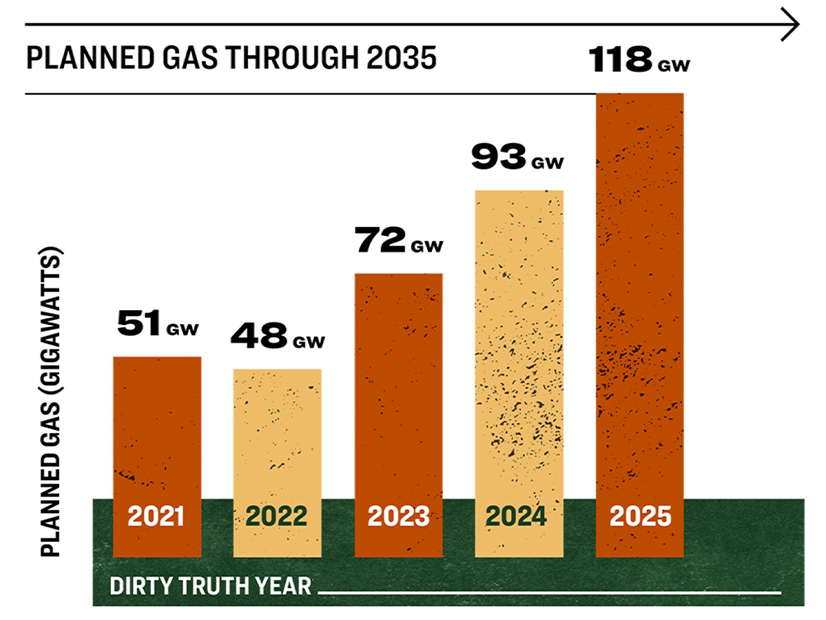

MISO has slashed earlier renewable energy estimates and boosted natural gas contributions in its transmission planning futures in a rethink brought on by the Trump administration.

Director of Economic and Policy Planning Christina Drake told stakeholders that MISO took a “very hard pivot” to incorporate the One Big Beautiful Bill Act into its four, 20-year futures, which are used to plan long-range transmission.

MISO was on its way to completing the futures and publishing capacity expansion estimates when the bill was passed in July. Staff have added months to the process and expect to deliver final futures sometime in early 2026. (See MISO Seeking Realistic Gen Buildout for Tx Planning Futures.)

“There is quite a bit of reduction in some of the renewable buildout,” Drake said before a Sept. 24 stakeholder teleconference. She also said MISO is reflecting increases in natural gas buildout in its members’ resource planning.

MISO Senior Manager of Policy and Regulatory Planning RaeLynn Asah said gas now represents a much higher share of the capacity expansion than when MISO last updated its futures in 2022.

MISO’s preliminary capacity expansion estimates by 2045 now include:

-

- For Future 1, a total of 383 GW in installed capacity derived from 28% gas, 25% solar, 25% wind, 11% other, 4% battery, 4% nuclear and 3% coal at 911 TWh of output, with 224 GW built between now and 2045.

- For Future 2, a total of 403 GW in installed capacity from 25% gas, 25% solar, 30% wind, 11% other, 3% battery, 4% nuclear and 3% coal at 1,075 TWh of output, with 254 GW constructed in 20 years.

- For Future 3, a total of 446 GW from 19% gas, 31% solar, 29% wind, 10% other, 3% battery, 6% nuclear and 1% coal at 1,253 TWh of output, with 318 GW built between now and 2045.

- For Future 4, a total of 454 GW from 25% gas, 33% solar, 20% wind, 10% other, 3% battery, 4% nuclear and 4% coal at 1,079 TWh of output, with 281 GW constructed.

MISO’s futures are fashioned through a “fast, faster, fastest” methodology for fleet change and demand in Futures 1-3. Future 4 — new for 2026 — anticipates continued supply chain hindrances and only includes member-announced generation retirements. Unlike the other futures, it doesn’t assume age-based retirements of thermal generators, resulting in about 23 GW of additional thermal generation compared to the other three futures.

MISO’s members have announced intentions to build 171 GW in resources by 2045. MISO’s modeling had to add the most supplemental resources to Future 3, where only 58% of capacity needs would be met using the 171 GW.

The RTO’s fleet prediction in 2022 under Future 2 for 2042 was 471 GW of installed capacity, consisting of 14% gas, 24% solar, 34% wind, 11% other, 9% hybrid resources, 6% standalone batteries, 2% nuclear and 2% coal. That future formed the basis for MISO’s nearly $22 billion long-range transmission plan for MISO Midwest.

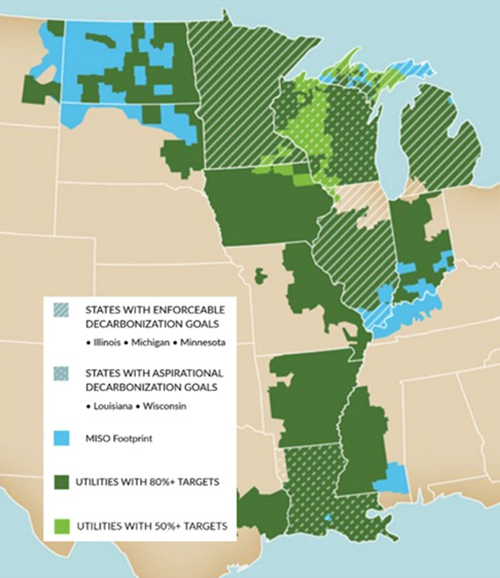

MISO said sustainability goals from states and members, not federal incentives, would drive future capacity expansion.

Drake said as it stands across all futures, milestone goals from 2026 to 2028 in Illinois’ Climate and Equitable Jobs Act and New Orleans’ renewable portfolio standard were unattainable. MISO said lead times to build units made the goals infeasible in the near term. Illinois has set out to achieve 100% carbon-free energy by 2050, with interim targets of 40% renewable energy by 2030 and 50% by 2040. New Orleans, on the other hand, is attempting to achieve net carbon neutrality by 2040 and 100% carbon-free electric generation by 2050.

MISO’s Environmental Sector requested a sensitivity study on the futures where natural gas prices rise, prompting an energy storage expansion.

Sustainable FERC Project’s Natalie McIntire said she wondered whether the futures for use in scenario-based planning should be more “diverse” from one another and contemplate a wider range of possibilities. She said MISO should contemplate variables like rising gas prices and falling battery prices, along with the possibility of a reinstatement of tax credits for renewables.

Drake said MISO will check in with stakeholders once futures are more developed. She added that MISO planners have asked themselves the same questions.

“If we get to the end of this process and we don’t have broad bookends, we will revisit,” Drake promised. She stressed that MISO’s numbers aren’t final yet.

Drake said MISO is halfway through the recalibration of its futures. She said initially, removal of tax credits for wind and solar resulted in MISO’s model building a hypothetical 100 GW within a single year to take advantage of the fading perks. Drake said after MISO staff “laughed” at the results, they removed the possibility for renewable production and investment tax credits for generation not already in the queue.

“The rationale for that is if it’s not already in queue … it won’t be in the ground and ready to go by 2028,” she said.

Drake also said MISO must complete generation siting and large load siting for use in its transmission models alongside completing energy adequacy assessments to develop the futures. She said MISO would discuss the locations of large loads in the footprint in November.

MISO Senior Vice President of Planning and Operations Jennifer Curran said members recently have swapped lower accredited renewables for higher accredited dispatchable plants in their plans. She also noted that the U.S. Department of Energy has become “directly involved” in resource retirements, issuing a second extension of Consumers Energy’s J.H. Campbell coal plant in Michigan.

“There has been a lot of activity on the federal front,” Curran acknowledged at a Sept. 17 Advisory Committee meeting in Detroit, part of MISO’s quarterly Board Week.

Curran said it became apparent that a repurposing of futures was necessary in July, when the early expiration of tax incentives became clear.

“We’re putting a lot of eggs in the gas development basket,” Clean Grid Alliance’s Beth Soholt said in response to MISO’s remarks, asking whether the RTO would factor in pipeline capacity issues and fuel availability limits.

Curran said MISO would try to capture the fuel availability associated with “explosion” in gas development and pipeline constraints in the resource’s capacity accreditation.